This is another one of those apparently genre-redefining films that all the first-run critics praised. Most of the genre critics have since torn this film apart, the better to examine its undigested stomach contents. I was going to do that, too. But my fellow Cold Fusioneer, MonsterHunter, already did. So go read it. It’s awesome. And it leaves me free to do my own damn thing.

As my colleague noted, George Romero’s Dawn and Day of the Dead played Alex Kintner here, inspirations director Danny Boyle rightly copped to early and often. He and I share a love for Day of the Triffids, and while he’s never mentioned Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth (to my knowledge), I’ll bet we both watched that at some point in the mid-to-late-80s.

Boyle was directing TV movies at that time, a job designed to make people wish for some population-flattening apocalypse. Then he hit what he must’ve considered “the big time” with Trainspotting, a movie about Scottish heroin addicts so honestly well made even American heroin addicts managed to work up some small spark of interest in it. For a moment there in the early 2000s, Trainspotting became part of a Unholy Trinity of Awesome movies every member of my small, real-world-based subculture championed, whether they liked talking about movies or not. Most didn’t, but I kept my ear to the ground and eventually rumors swirled that the guy who did Trainspotting was making a zombie movie. How could that be anything less than awesome?

Well, because it’s a compromised, redundant little film made by a director who’s only ever been as strong as his source material. That’s how.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: three animal right’s activists invade an English research laboratory apparently dedicated to recreating that subliminal conditioning head brace from A Clockwork Orange. The three activists (played by Alex Palmer, Bindu De Stoppani, and Jukka Hiltunen), who obviously don’t deserve names because the entire civilized world decided animal rights activists were less than human sometime in the late-90s, release a chimp infected with “Rage.” Twenty-eight days later, dot-dot-dot, the Rage Virus has reduced Britain to an abandoned ghost country.

Comatose bike messenger Jim (played by future Scarecrow Cillian Murphy) wakes to this new reality and soon meets up with The Infected (though certainly not soon enough for those used to zombie movies that open with gunshots, suicidal priests, or corpses-in-a-can). The Infected, in their turn, chase Jim toward fellow survivors Selina (future pirate of the Caribbean Naomie Harris) and Mark (Noah Huntley), who fill Jim in on all the wonderful fun he’s slept through.

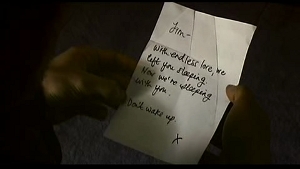

Keen to find out what happened to his parents, Jim and this Army of Two return to Jim’s parent’s house, finding them long dead from quiet suicide. The love note they left him ends with the best possible advice they could’ve given their son under the circumstances: “Don’t wake up.” Being an everyman who slept through that interesting slice of time where most zombie movies take place (rather like a mainstream audience member who’s never seen Night, Dawn, or Day of the Dead, eh?) Jim’s faffing about eventually attracts the Infected. Here we learn two very important things: 1) this movie did indeed have a gore budget, and 2) it’s the way they deploy their gore that so initially shocked people…and by people I mean “people who’d never watched a movie with the word Cannibal in the title.” You know: freaks.

All of which is a wonderfully round about way of getting Selina to hack Mark up with a machete. “He was infected!” she tells Jim. “I could see it in his eyes!” Any contact with infected fluid results in immediate zombiefication. You have twenty seconds before Rage turns that normal person you knew and loved into a snarling abomination with an irresistible urge to puke up blood and do grievous bodily harm (mostly offscreen, the way British censors like it) to any non-Infected they can catch.

We’re left, then, with the oldest conflict in the modern zombie movie Rolodex: to ensure the survival of humanity, must we become less than human and mercilessly slaughter the ones we love? The abyss gazes also and whoever fights monsters and blah-dee-blah-dee-blah. What’s this? Dramatizing a hundred-year-old philosophical conflict in a monster movie? <sarcasm> Oh, how avant-garde.</sarcasm> No wonder this thing won a Saturn Award.

I can understand why that happened. Its relatively low budget assured a tight focus on putting characters through what some call “a plot,” when they’re being charitable. Not, as is so often cited, a “tight focus on the characters.” Because 28 Days Later had enough brains to steal from George Romero, they knew their plot would have to build inexorably toward a justification of their thesis. What thesis? Oh, c’mon; you know this one, right? Why do you think they called it “the Rage Virus?”

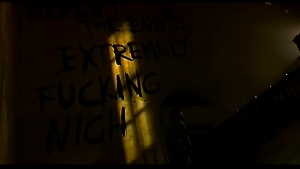

Because civilized humanity is a false facade, imprisoning the raging beast of pure, instinctual snarls that dwells within every single one of us…right? Are you nodding in sympathy with that sentence? Well, congratulations. You’ve obviously imbibed our alien overlord’s subliminal messages. I’m supposed to be unnerved by 28 Days Later‘s message, just like I’m supposed to jump and go “eww” at the all blood vomiting. Well, screw you, 28 Days Later. I’ve seen two many horror films push the same damn party line. These days, I root for the zombies in these things by default. All you’ve done is make them more sympathetic by making them poor, pathetic wretches with no choice but to assault whoever. Hell, in this Britain, they’re the majority, harassed by terrorist cells of so-called “normal” people who immolate them with Molotov cocktails. So don’t give me any of that “powerful metaphor for our time” shit the keyboard monkeys churned out of Sundance.

We’re all monsters, don’t you see? Is that not the theme of Modern Horror? Can’t you see it now from our high vantage point in the twenty-first century? Look across this blasted landscape of pointless remakes and perverted sequels. What do you see? I see a pack of stupid movies looking to encourage my sloth by confirming all my worst prejudices about the human race. All 28 Days Later did was apply that to the zombie film template.

If that’s all one needs to do to “re-invent” a genre, so be it.

Anywho, Selena and Jim hook up with Frank (Brendan Gleeson), the last taxi driver in London, and Frank’s teenage daughter Hannah (Megan Burns). While international communications are still out, Frank has discovered a shortwave broadcast emanating from somewhere near Manchester. An army detachment claims to have the cure for infection. With four people, Our Heroes just might make it there alive. Certainly can’t stay in the city. The vampires ghouls goblins possessed Infected already own the night and the rains refused to come, making fresh water a problem. Natural forces reinforce the supernatural (or Super Scientific, in this case) Horror that’s come callin’. Gee, how original. Not like every giant monster movie ever made has ever tried that before…

After a brief bit of thievery homage to the shopping scenes from Dawn of the Dead, Our Heroes begin their road trip through the deserted English country side. We get a wonderful scene where the four gallivant through a field (joined by four horses who’re also gallivanting through a field and Keenan Ivory Wayans shouting, “Message!” at the top of his lungs) and Selina pecks Jim on the cheek. He blushes like a big goof and it’s astonishingly wonderful to see the film’s Love Interest flower at such a naturalistic place, and with such small bits of business. Love Interest is not the plot. If this were a bad zombie movie, it would be. (Unless that movie’s Shaun of the Dead, which would come out two years later.) Boyle made sure to follow Romero’s (20th century – he’s gotten sloppy in his old age) rules of character development and that save the film from completely pissing me off. No one gets any stirring speeches or evocative backstory monologues (except for Mark…and we saw what happened to him); everyone’s allowed to show who they are through their actions. Unless those actions result in a loss of their cool, in which case, they’re zombie chow…but that’s just one more box on the checklist for this flick.

Then the movie ruins its own cred by ripping off Dawn of the Dead‘s Spring Loaded Zombie Child at a Gas Station moment. Jim fares no better with this than Peter did, back in the Romeroverse, but at least he doesn’t point a gun at anyone. No guns to point in England. It’s all blunt instruments and big knives for Our Heroes. Until they meet the army.

Ah, the army. Led by Major Henry West (future Dr. Who Christopher Eccleston) (and can you dig that name? “Designated Human Villain in a Zombie Movie” would’ve been far too cumbersome and obvious, even for Boyle), the army detachment of Manchester’s managed to barricade themselves into an isolated mansion. Cut off from the world, Major West maintains order by letting the boys vent their rage (see what I did there?) on the Infected…and promising them women.

So “the solution to infection” is gang rape. Again, we’re supposed to be shocked and appalled at the depths Our Brave Men in Uniform will inevitably sink to in the event of an apocalypse. Your surprise will probably depend on the number of Westerns you’ve seen, or your knowledge of what Our Brave Men in Uniform are already capable of, apocalypse or no. What else are a group of armed men outside the bounds of civilization going to do with civilians? I know I’m not the only Trekkie who watched Night of the Comet. (Because I watched it with at least two others.)

There are at least three endings to this movie because test audiences didn’t like the first one. Even if I didn’t already remember that from 2002 (I prefer the 2003 ending, myself) I’d be annoyed with the entire third act, which never reaches the horrible heights its well-constructed opening promised. I’m with Ebert on this one: I wanted that plane to strafe our survivors with daisy cutters. Before that, though, this movie already had me bleeding from the nostrils. Can’t be helped: I’m allergic to movies that are made from parts of other movies. Blame Roland Emmerich. I do.

You might not know it to look at this script, but Alex Garland’s an actual author, and we authors are all taught to steal as best we can, from as many sources as possible. Unfortunately, we can’t dress up our theft in purple prose and intimate character examinations when we’re working in the Medium of Cinema. As proof of his bona fides, I present you with The Beach, the book Boyle’s previous film was based on…all coming together now, isn’t it?

Danny boy apparently fucked with Garland’s original ending to The Beach, probably because test audiences thought it was “too dark” for their tiny little minds. So Garland re-stages it here as the climax of a zombie film, with Jim going as mad as the Infected soldier he lets loose upon Manchester’s would-be gang rapists. It’s either Boyle’s way of saying, “My bad, bro,” to his friend the writer, or Garland’s way of saying, “Damnit, Danny, either you film this or it’s pistols at ten paces tomorrow morning.”

The Beach, for those who don’t know, starred another Blank Slate (played by this critic’s least-favorite Leo) who, like Jim, dips his toes into a beloved exploitation genre (the White People in Peril movies most people call “thrillers” nowadays) before freaking out in the last act after The Horror proves too much for him…and not nearly enough for us.

So while I’d gladly back Colonel Ebert’s air strike, I can’t call this film “tough, smart,” or “ingenious.” Any given Italian horror movie is “tougher” to sit through, whether it contains zombies or otherwise. I reserve the label “smart” for zombie movies that have something to say George Romero didn’t already say twenty years prior. And while this does not diminish it as a practical accomplishment of Herculean proportions, the only ingenuity I see here was budget driven.

Because they didn’t have money for make-up, these zombies are unrecognizable to most on-the-street zombie fans. Because digital video was cheap, Boyle shot the movie in grainy docu-vision, with hand held cameras that don’t capture the Infected’s motion blurs, making them look all the more like rag dolls or extras from a music video. The immersive properties of hand held cameras are severely overrated, though their inherent sloppiness is a great boon if you’re trying to hide practical effects. Boyle only rang honest tension out of me during the Flat Tire Scene…which he went so out of his way to contrive even Jim comments on how much of a “shit idea” it is in his one (thankfully temporary) lapse into Authorial Cipher Mode.

Conversely, Boyle’s portable camera work lends a dissociative air to dialogue scenes, dragging me out of what would otherwise be a trite but serviceable post-Apocalyptic character study. Against all my better instincts, these characters did manage to grow on me, and I did wind up genuinely rooting for them. If only the damn camera would settle down and stop trying to give me a headache.

Really, I’m just pissed at the movie’s marketers. I’m pissed at all the people who call this their favorite horror film and don’t know how much that says about their own shocking ignorance. This movie was doomed from the moment people started imitating its aesthetics, primarily the “running zombie,” as if this film created that, too. I’m not even willing to give it that much.

Some people really liked this flick, though, and I can see why. It’s the Independence Day of zombie movies: a compilation of the genre’s greatest hits. If you don’t have the time or inclination to watch them all, give this a go. You’ll be well on your way to being as cynical and contemptuous as the rest of us. Especially if you screen Romero’s original Dead trilogy (or even Tom Savini’s remake) immediately before or after this flick.

It has its moments, mostly in the middle, after our core foursome achieve some manner of equilibrium. Boyle just can’t seem to help himself but fuck with them in ways that seemed icky to him and seem hilarious to me. This is, after all, the man who attacked Ewan McGregor with a dead baby, thinking it would be frightening instead of knock-you-on-your-ass funny. The increased speed of zombie pursuit does not alter the been-there-seen-that feeling of everything else here.

I can’t help but conclude 28 Days Later got a lot of points just for existing. If it were anything other than a British indy horror movie, I doubt we’d remember a damn thing about it today. Unfortunately, it made money during a recession (not the last one but the one before the last one) which means we have it to thank for an entire generation of zombie movies…and most of the things that so piss me off about them. But that’s a rant for another time and a more deserving target, named Boll. Or Snyder.

![]()

![]()

![]()

I don’t get your…pardon the pun…rage at the film itself. The marketers? Sure. But that’s what they do. The fact that a movie that wasn’t (yes, I’m going to make this case) actually a zombie movie, but more part of the smaller subset of “people with diseases that make them go violently crazy” flicks that also houses The Crazies, and that one with Yaphet Kotto and Sam Waterson that scared the living shit out of me as a child (Warning Sign, I think is the title), lead to the modern zombie craze does annoy me, especially since it’s rampaging, running psychos got co-opted by the Dawn of the Dead remake that also sealed forever into law that all zombies=people with viruses that kill and reanimate them, whatever the fuck that’s supposed to be. Bah. But this actual movie? Admittedly I only saw it once, but I quite liked it. I liked the characters, I rooted for them, I was saddened when Gleeson buys it. Yeah, the last act was a tired rehash of overused cliches…I can get behind that. But up until that point I thought there was, for a change, genuine suspense and thrills. I think the ID4 comparison is a little harsh, though the film certainly makes its strategic lifts (my favorite being the Day of the Triffids one, going back to the granddaddy of all of these stories).

Also: thrillers? Weren’t they always pretty, usually white, people in peril films?

Sorry to give the impression of rage. I was aiming more towards “contemptuous dismissal.” That’s the beauty of subjectivity. Hell, some might mistake that ID4 crack for a complement.

And there you go, stumping me again, since I’ve never seen The Crazies or Warning Sign (which is indeed the title) Though the latter immediately wins my vote by virtue of its Yaphet Kotto.

Well, the “rage” was just a cheap excuse to make a joke. I don’t agree with you that this needs to be contemptuously dismissed, but, yeah, “yay subjectivity”.

Going by my memories of Warning Sign, which I saw at least one more time when I was a bit older, it’s essentially the T.V. movie version of The Crazies and Kotto doesn’t get a major role. If I’m remembering it right he’s basically the man on the outside-see, Warning Sign takes place in a research facility that’s successfully locked down, and Kotto is the guy the government sends to keep it that way. Sam Watterson is the sheriff whose wife is stuck inside. It’s a race against time to find a cure for the disease, which turns the victims into psychopaths. The original The Crazies occurs right in the middle of rural PA and the government ineffectually tries to lock it down (though they also send in a black officer to lock it down…I really wonder if the makers of Warning Sign hadn’t seen Romero’s film, or at least read a synopsis) and that film is as much about the bungling of everything as it is about the horror of the event itself. I do like that Romero’s virus makes people go crazy in very variable ways, which makes it hard to tell at any one point who has “the bug” as they call it in the film so often, and who just is stressed out because, hello, ineffectually run quarantine and surrounded by crazy people? I really need to see Warning Sign again, but at the time I saw it (I might have been 9 or 10) the idea of a virus that makes people act on their most violent urges scared the shit out of me at the time as it was a new idea. Reading some reviews it sounds like they keep some mystery about exactly what’s going on at first, which checks with my old memories of it, and are initially focused on the lock down procedures and the fact that what the town thinks is an agricultural lab is actually a bio-weapons lab.

Anyhow, it could be the vital link between The Crazies and 28 Days Later, or there may be better, more obvious links in bringing the “virus that makes you lose your mind” to “virus that makes you homicidal” to “virus that makes you a killing machine that’s all dirty and bloody and blurry and kinda like a zombie if you gave zombies meth.”

I have to agree, 28 Days Later is actually a prety good movie. Is it derivative? Sure. But at least it’s good derivative. It’s got Brendan Gleeson, who like Yaphet Kotto or Gene Hackman makes every movie he’s in a little bit better. The digital video works for me. The scorn you placed on the animal rights activists I put squarely onto the idiots making the Rage virus in the first place, so it’s not as offensive to me. And Naomie Harris does a bang-up job too.

The “are we all monsters” plot is been-there done-that, but it’s execution is what saves the movie for me. The little touches. Put good actors into a mediocre plot and you end up with a good movie, right?

Now that, Steward, is a very good question. Can good actors save the mediocre plots they’re in? And when’s the last time a movie managed that trick? I encounter the opposite more often than not: half-decent plots saving mediocre cats from complete ignominy and occasionally launching careers. Nightmare on Elm Street 3‘s the example I always go to. But it’s early yet, and I haven’t had near enough coffee.