If you were alive on planet Earth in 1993, you probably found yourself face-to-face with the work of Michael Crichton. He was fifty-one by that point, and a multiple New York Times bestselling author with a shelf’s worth of fiction and non-fiction to his name. Most didn’t bother looking at them, but some of us did, and through them we learned Jurassic Park was the end point of a thought-line that runs through Crichton’s whole career, possibly his entire life.

To tease that thought-line out, it’s best we step back into the shoes of a thirty-one-year-old Crichton as he attempted to become a full-time filmmaker. It’s 1973, and Crichton’s last two books are doing well, though nowhere near as well as his first real success, The Andromeda Strain. Published in ’69 and made into a movie two years later, Strain contains the seeds of Crichton’s literary obsessions…though neither book nor film are as thrilling as they think are.

Which is probably why his next book, Binary, reads more like an episode of CSI than as an actual Michael Crichton novel (and since it was the last one he published under a pseudonym, that kinda fits). Police procedurals always sell, especially when they can wow the audience with all that fun, new forensic technology modern cops (supposedly) get to play with these days. So Binary became a made-for-TV movie, re-titled Pursuit, with Circhton himself directing.

Having proven his chops, Crichton began shopping scripts around Hollywood, including an idea inspired by Disneyland’s Pirates of the Caribbean ride and its “impressive” anamatronic characters. Combining his love for the technological underpinnings of modern life with his love for kick ass movies, Crichton came up with Westworld and – through some no doubt-arcane magic – convinced MGM to let him direct it with what certainly looks like minimal supervision. Name another SF author who can say the same thing?

The result is a strange movie – simultaneously innovative and retrograde – that you can appreciate on a lot of levels. At base, it’s a straight-up Western. Above that, it’s a low-key buddy comedy. And above that, it’s a sci-fi scare-fest. And above all that, it’s keystone of Crichton’s literary work. Not just because it deals with his primary storytelling obsession – the pathological failure of modern society’s complex systems – but because it explicitly depicts the consequences of those failures in a way The Andromeda Strain couldn’t, since its antagonist was a space virus. Here, the fundamental entropic principals of the universe have a name and a face. Luckily, for you The King and I fans out there, both belong to Yul Brynner.

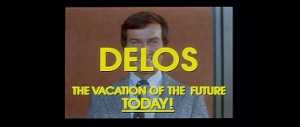

Before we get there, we start off with another Crichton-trope: false documentation. The novel Jurassic Park (for example) starts off with a long-winded-but-still-abridged history of genetic engineering and the biotech companies that grew around it. In this case, we get an informercial for the Delos corporation, introducing us to Delos’ futuristic theme parks: Medievalworld, Romanworld, and Westworld. Decked out in (the then-popular culture’s prevailing notions of) period-specific décor and peopled by highly advanced robots, these parks promise all who enter “the vacation of tomorrow, today.” Visitors are free to indulge their every whim, secure in the notion that “nothing can go wrong.”

Two such visitors give us our in-road to this world: apparent best friends Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) and John Blane (James Brolin). John’s been here before, and so assumes an easy, know-it-all air that can become insufferable after awhile. This is Peter’s first time, so he gets to be insufferable right from the off, peppering John with the kinds of questions hapless schlubs would ask on the hover-craft ride over. Thanks to way Crichton lingers on these two, the scene perfectly recreates the feeling of being trapped on a flight next to some asshole who just won’t shut the fuck up.

Landing, John and Peter change into appropriate attire and integrate themselves into Westworld, with John being more successful than his friend, who feels “silly – like a joke.” John’s response is priceless:

“It’s not a joke! It’s an amusement park! All you have to do is have fun.”

“Fun,” in this case being defined as “drinking unlabled rot-gut whiskey, getting into random fights, and sleeping with robot whores in too-small, nineteenth century beds.” Because whenever a new technology comes along the first question anyone asks is, “Can I fuck it?” Or you can out-draw the Yul Brynner-bot in a slow motion-assisted gun battle. Don’t worry: the robots are programed to make sure you always win. After night falls on this day of Peter-mollifying merriment, the Delos Corp. elves come out of their control tunnels to clean up the robot bodies and ship them downstairs for repair.

If you want to see a sci-fi movie with a real “documentary feel,” look no further than this almost forty year-old Michael Crichton flick. These little asides in the control room will punctuate the main action from here on, and the camera becomes one of those roving eye-ball things Darth Maul had in the middle of The Phantom Menace: floating over technicians with handfuls of android guts; lingering on the eery sight of Yul Brynner-bot’s unhinged faceplate; tracking the head technician as he pokes and prods his subordinates. “You get a confirmation before you open her up.” “Yes, sir.”

This is the reason Crichton became a novelist instead of a doctor. At some point during his rounds at Boston City Hospital, a younger version of Crichton looked up from whatever he was doing and saw this:

And in that moment something simple, basic and human in his mind recoiled, stunned by the horrifying banality of it all. He decided to share this vision with the world, almost always casting it as a vision of our future. The present is (usually) far more marketable when you dress it up in future-garb. But for all the random SF elements casually tossed into the background, for all his technical lectures (the long moments of silence in this film are perfectly designed for a scientific/historical aside) and one-note characters, there’s a humanist core to Crichton’s work that’s so subtle most people don’t bother noticing it. He spent his whole career trying to warn us this future has already come to pass. And we’re living in it. Or at least trying to. It could very well gun us down in the street at any moment without thinking twice and that’s so scary a thought, most of us turn away from it…giving this present-future the perfectly opportunity to bite us in the ass.

So it is with Our Heroes, Peter and John, who survive the Obligatory Bar Fight and spend the night on the floor. By now, both are fully into the spirit of Westworld. What better time for the androids to rise up against their human “guests”?

We never really know how or why the robots of Delos suddenly go mad. The programers and scientists behind the scenes talk of a virus spreading through the robot population, but its structure and origins are never explored. There’s no Dennis Nedry in this movie. Most of the people in Crichton’s early novels were well-meaning but useful idiots instead of active antagonists. The turning point (when Crichton took his first half-hearted stabs at creating “villains”) probably came with either Congo or Sphere…though in Sphere, everyone’s driven mad with power, so you could call all of them “antagonists” if you really wanted to get technical. (Spoiler alert for a twenty-five year-old book and fifteen-year-old film, neither of which are the strongest entries in their creator’s catalogs.)

You could say the same thing happens here, only with less reality warping and more accidental suffocation. Before that, though, Crichton’s careful to show us a scene where the technicians down below talk themselves out of recognizing the problem…or even out of the fact that a problem’s occurring. After all, robots can’t catch viruses…not like, real ones. After all, the use of the term “virus” to describe malicious, self-replicating computer programs had just entered the popular SF consciousness in 1969 and wouldn’t escape its genre ghetto for another eleven years.

In the meantime, we see brief shots of the robot apocalypse going on in Romanworld, but Crichton’s never really been interested in the nitty-gritty of robot-on-human (or anything-on-human, for that matter) violence. He had a clinical view of the human body and it’s various bi-products, which tells you why his characters are all so forgettable…apart from the occasional Author Avatar. (Here’s looking at you, Dr. Malcolm…and your damned gymnast children.) Peter and John come off as dudes playing cowboys, which is exactly what they are and exactly what they need to be…but that’s pretty much all they do for the whole movie, one hesitantly (at first) and the other enthusiastically. This evil robot, on the other hand, is one cold bastard, and you can tell Crichton loved exploiting this concept to its fullest. I wouldn’t call Brynner-bot a “character” per se, but Crichton’s greater interest in filming “him” at the expense of the home-grown humans is more than evident. Inexplicably (if you’re working off an Asimovian background, like yours truly), Brynner-bot seems to like toying with his prey, showing off and wasting ammo as only a Western badass can. Whoever programed him obviously loved The Magnificent Seven as much, if not more than, my parents.

Thanks to its SF trappings, Westworld‘s not often given credit for being both a functional Western and a send-up of Westerns in general. As with other writer/director luminaries of the 70s, Crichton grew up watching Western movies, serials, and now-classic TV shows. This is his cinematic love note to his own childhood, and it’s telling he made this as soon as he got the opportunity (re: cash) to make it right. Every genre touchstone is here, from the whores to the gunfights to the Sheriff-killings to the jail breaks. And what to our wondering eyes should appear at the very end? A showdown between the Big Badass and the Kind-Hearted Tenderfoot, of course. John Ford would nod in stoic approval…at least until our Tenderfoot reaches the underground lab.

Even then it works because, clinician though he was, Crichton could also be a ruthless sum’bitch when the need arose. Exhibit A: the poor White Shirt Yul Brynner-bot catches in the desert and perforates from half a county away…because that’s what he does. As human as he may look, he and all the robots of Delos lack the basic human ability to countermand his own programing. That’s why they have remote control off-buttons…and those might’ve worked too, if it weren’t for that meddling virus.

That virus represents any random element intruding upon humanity’s best laid plans. The cautionary air to these tales is sometimes mistaken for technophobia, but I’ve grown to see it as a more straight-faced, if no-less-strident, warning. “Please,” Crichton’s stories beg us, “take a look around yourselves. Peep the vast, complicated, technological systems that underpin your life and lives of every human being on the planet. Check ’em and respect ’em, because learning shit is cool…and because those systems have no respect for you. Unless you pay attention, one of these days, you’re going to wake up and find they’re out for your blood.”

That’s the real message of his fiction and thanks to this, Crichton stories have a nasty habit of fading into each other. Being the oldest of his “mature” work, Westworld‘s suffered from a lack of attention. It deserves to be seen by all Crichton’s fans and by SF fans in general. It’s early 70s pacing will try the patience of nincompoops and its disinterest in human beings has left the actors high and dry. Thankfully, we’re in the hands of a great cast, with some of the best leading men of the late-60s. None of them ever became the Marlon Brando they wanted to be, and I’m sure certain people thought Yul Brynner’s best years were behind him…but they were wrong. Everyone ran with it, had fun, and created a creepy-fun thrill ride through an under-appreciated classic from everyone involved…especially its writer/director.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One of my favorites. As a lover of The Magnificent Seven myself, I really the appreciate Yul Brynner playing a badass gunslinger cutting down the unaware populace.

My enjoyment also comes from Romanworld and Medievalworld, one for the girls who wanted to be princesses and one for the men who wanted real live orgies next to the vomitorium, one suspects. Crichton really did understand what an adult amusement park would look like. When I was younger, I really enjoyed most of his novels, especially The Andromeda Strain and Congo. Now that I’m a little older, I find his books to be so didactic that I can’t read them anymore. One gets the idea that Crichton thinks the only reason the planet can still support life is the dire warnings he gave us in his novels. Between bioengineering, evil Asians, big airplane manufacturers, and grey goo I’d have thought we’d all be dead now.

To say nothing about the wild velociraptors running around the jungles of Costa Rica, getting lysine from people’s corn.

It really says something that I find the book about time travel to be the most believable of his work over the last twenty years or so.

Although I never saw E.R. I suppose that one may have been believable.

As realistic as any other prime time Medical Drama. For whatever that’s worth.

Yul Brynner is really what makes this movie work. He’s not just a homicidal robot. He’s downright chilling, intimidating in the same way Arnold was in the first Terminator film. That in itself is pretty impressive, because he doesn’t get to make shows of inhuman strength the way Arnold did. He does it all with acting, and he didn’t really have much help from the script.

“this future has already come to pass. And we’re living in it”

I’ve been trying to tell people this for like 15 years now, nobody believes me…

Good review, good movie.

One thing that really urked me about Westworld is that when the robots start revolting , signalled by the robot rattler biting the guy, the guests’ robot horses still obey. Why wouldn’t they buck the riders off and trample them ? It goes to show thatthe scriptwriter never thought the premise through logically.

Daniel: Yeah, without Brynner-bot, this flick probably wouldn’t even exist in the first place. I’ll bet the Westworld pre-production office had one hell of a party (fit for Ramses II!) on the day Brynner’s agent called to confirm his involvement.

Rizzo: I believe you. And believe me, I know exactly how you feel.

Sandra:…or that the production itself didn’t have the money to keep those horses around for the climax. In Hollywood they tell you, “Never work with animals or children,” the big reason for that being, “Because everything will automatically take twice as long to pull off as it would otherwise because (in this case) you’ve suddenly got to deal with a herd of 500 pound animals on top of all your every day, movie set chaos.”

Me, I’d be more than happy to see big ticket massacres in all three worlds, but time and tide being what they are, we’ll have to content ourselves with little flashes on monitor screens. And one sword fight with the Black Knight.

I reviewed this one early in my current blog’s history, but lacking your background in Crichton (I’ve never read any of his books and have seen few of his movies) I spent the time questioning the whole concept of this film a lot. Sure, the heat sensors stop you from shooting paying guests-but how do you avoid accidental shots? How do you stop guests from stabbing/slashing one another to death? You can create sex bots but you can’t make convincing hands? I felt the film gave me too much time to question how all this stuff worked, but maybe that was just me. I did enjoy the central Benjamin vs. Brynner conflict…pretty hard not to, and its so good its influenced everything from slasher films to sci-fi.

It wasn’t just you. Crichton seriously needed someone to sit him down and give him a lecture about the differences between cinematic and literary pacing. He always preferred going about things methodically, which is why so many of his novels fit my dictionary definition of “a pot boiler.” Once they get going, they stay gone, but the process can take for-fucking-ever. This is especially true of his pre-Congo and post-Lost World periods, but all his work is didactic as hell, and that can irritate just as easily as it engages. I’ll bet you any novelization of Westworld (which, my research indicates, don’t exist, though the screenplay was apparently released as a paperback in conjunction with theatrical run) would’ve brimmed over with technical asides designed to address just those questions…and probably a whole lot more we haven’t even tried to think up.

Just a quick comment on your take on Crichton’s over-arching theme to his writing. I agree that he loved technology but didn’t trust mankind with it. And if you’re right that he was trying to get people to wake up to the world around them then its the height of irony that one of his lasts books, State of Fear, is about the “eco-conspiracy” surrounding climate change. He finally has proof positive that he was right all along that humans don’t have a clue about the repercussions of our actions and yet he didn’t have the guts to write a story about runaway climate change. Instead he writes about eco-terrorists trying to cause global warming to prove they were right and the oil-men were wrong. Really, Mike? You’re going to shuffle off this mortal coil undermining the whole body of your work? That seems pretty silly to me.

Of course, I am questioning the motives of a man who said cloning dinosaurs and keeping them in a park is a bad thing. And that’s just crazy talk right there. I want my Brontosaurus ride and I want it now!

You and me both. No matter how many times I see a “2” at the beginning of the calendar year, I refuse to believe I’m living in “The Future” until a dinosaur theme park opens up to the public.

As to State of Fear…I’ve never read it, Timeline, or Next and can’t remember a damn thing about Prey (save a vision of someone with a face made out of nanobots), though that’s probably because I read it in December, 2003, a blurry month of overnight shifts stocking retail shelves for the Christmas season. That’ll fuck anybody up, and people start to look like they’ve been replaced by evil Replicants anyway.

And I don’t regret it for a moment. The Lost World (the book) really shook my faith in our Mad Mike, and I fell out with him completely after he wrote that punishing exercise in tedium, Airframe. I looked on most of his later career from a place of bemused ignorance and when State of Fear dropped…honestly, I wasn’t all that surprised. This is the guy who wrote Disclosure and Rising Sun, after all…which I literally just realized I’m going to have to review at some point…shit.

My favorite Crichton book is Eaters of the Dead. I’m not sure what the technological threat in that one was. It’s basically a shaggy monster joke told with a completely straight face. In his “bibliography” at the book’s end Crichton cites the Necronomicon as a source. In 1976 that was still a funny in joke.

It was adapted into the movie The Thirteenth Warrior. Antonio Banderas is kind of fun as the Arab ambassador who ends up stuck with the filthy Northmen.

13th Warrior is a movie my roommates watched over, and over, and over, ad nauseum. And yeah, it’s pretty enjoyable, a sword-and-sandal movie with Vikings instead of gladiators.

But really, Jurassic Park is about the last good book he wrote. I’m a sucker for authors I like, reading their books because I can remember the good stuff they did years ago rather than the current crap, and I think Crichton has caused me more pain than any other author. Andromeda Strain, Congo, Jurassic Park, Terminal Man, those are the good side. Lost World, Sphere, Timeline, Rising Sun, Prey, Next, Airframe, these are the crap side. Any day now, I’ll be at the library looking for a beach book, and I’ll pick up his pirate novel. Then I’ll hate it. Then I’ll hate myself for picking it up when I know what I’m in for.

Someday soon I’ll get drunk and go on my Tom Clancy/Dale Brown rant. Mark your calendar.

Nice review, David. There’s another Killer Robot b-movie worth seeking out called “Eve Of Destruction”, starring Gregory Hines and Dutch actress Renée Soutendijk. It freely apes from The Terminator, while throwing in some T&A and gloriously cheesy ’80s fashion and hairstyles. It’s not as action-packed as it probably promises, but there’s plenty of scenes that are just Wrong.

I vaguely remember hearing about that when it came out due to my mother’s standing crush on Hines and my father’s standing crush on anything tall, light and Nordic that caught his eye. I’ll be sure to add it to the growing stockpile of Terminator rip-offs. The more the merrier, since the more I have the longer I can avoid talking about the Rise and Fall of the Terminator Franchise-proper. At least until I feel the need to seriously depress myself.

Nifty review, been ages since I’ve seen this movie.

Any chance of a review of Futureworld? I’d like to see how you contrast it’s Invasion of the Bodysnatchers riff (as I seem to recall) to this movie.

We are all concerned with Futureworld, for that is where you and I will spend the rest of our lives.

The real answer is “Yes, undoubtedly.” In fact, I could probably do a whole month of nothing but sequels to Michael Crichton projects.

Definitely one of my favorite films. While the focus does center a bit heavily on the Gunslinger, rather than Peter and John, I really thought all three of the leads were well cast. Part of the reason I like it so much, I’m sure, is because of it’s similar themes to “Jurassic Park,” which I loved.

Another reason I would say is for the vague similarity it has with another of my favorite films, “Jaws.” Nowhere in the film do the battle a Great White, but the climax reminds me vaguely of “Jaws.” Since John is played by the macho James Brolin, if we’re expecting a final battle between the Gunslinger and a guest, we would naturally assume the guest would be John, rather than Peter, as John is the macho guy who is much more experienced in the inner workings of the park. Instead, John is killed early in the third act, and we’re left with the hapless Peter, whom we would never expect to have the guts and wits needed to take the Gunslinger down.

Similarly to “Jaws,” where Quint and Hooper are basically out of the picture in the shark’s final showdown, and it’s left to terrified-of-the-water Brody to kill the shark.

In both films, the script and performances go out of their way to establish both Peter and Brody as ill-equipped to take out the major menace, which adds to the suspense and joy when they both succeed in their respective films.

Much of the success of the film has to be attributed to the cast. Brynner, Benjamin, and Brolin are obviously having a ball, as are the rest of the supporting players. Bartold’s immediate cowardice when he’s threatened with a Black Knight that isn’t going to throw the fight this time is believable and realistic. Dick Van Patten really gets into the fun as well. Like Benjamin, he seems self-aware that this may be the only time he gets to strap on the guns and strut around like a western hero, and he makes the most of it.