Plenty of sci-fi properties obsess over the planet Mars but there was a time, throughout the early part of the twentieth century, when the planet Venus commanded similar attention. Obviously, this was before robotic observation revealed the 900 °(F) desert under those miles-thick clouds of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid. Damn place is hotter than Mercury once you get right down to it. But if you ever are magically transported to the surface, don’t panic: atmospheric pressure will crush you long before you have time to fry or choke on your own melting innards.

Nobody knew this in June, 1957, obviously. Sputnik was four months away from launch. Mariner-2 was five years away and scientists spent the rest of the 60s arguing about its data…i.e., doing their damn jobs. We can forgive 20 Million Miles to Earth its interplanetary ignorance. Especially since that ignorance doubles as the source of some truly batshit excuses for Science. And this is me talking: the from a man who thinks nothing of movies about dinosaurs spontaneously reanimated by atomic explosions. Unfortunately, this film signals a trend toward the same kinds of awful unthinking that kills genre movies to this day. It had all the elements of past successes, but the essential creative sparks that powered, say, Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, or even Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, obviously faded as the decade that spawned them wore on.

I name drop those last two because 20 Million Miles to Earth is another collaboration between Columbia pictures and stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, flowing directly from 1955’s It Came from Beneath the Sea. Which also happened to be Harryhausen’s first collaboration with producer Charles H. Schneer, who would go on to produce Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and every other memorable movie with Harryhausen’s name on it until 1981’s Clash of the Titans.

But first, they made this…with the director of The Deadly Mantis, one hungry young writer whose work I’ve never heard of (Christopher Knopf), and another, old hand writer of Westerns (Robert Creighton “Bob” Williams) whose work I doubt I’ll be covering again any time soon. By this point, sci-fi pictures were very good at making money quickly and the lure of quick money will always drag professionals from other disciplines into the pool, no matter how long they kick and scream. That’s not a criticism, merely an observation of the blindingly obvious, since 20 Million Miles to Earth‘s script is regularly weighted down with leaden exposition, dropped with all the subtlety of…a rocketship crashing into the Mediterranean. It’s the kind of stuff a first-year writing student piles on to disguise their own discomfort with the material, because exposition is easy. Writing monster movies is hard.

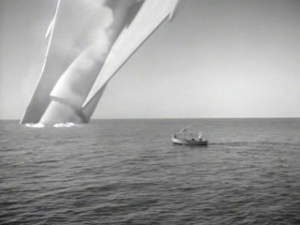

Therefore, after the Helpful Narrator (William Woodson) name drops the Atomic Age and the title of the film (that’s three drinks in the first thirty seconds for those of you playing the home game), we see that the United States of this wacky parallel dimension has managed to put a man on Venus. The “return him successfully to the Earth” part of the mission has some kinks left to work out, though, and the ship splashes down off the coast of Sicily. A pair of “Sicilian fishermen” (Don Orlando and George Khoury) rescue the two survivors before the ship sinks. The fishermen’s kid sidekick, Peppe (Bart Braverman), rescues a mysterious canister that washes up on the beach and decides to keep it for himself. Meaning everything that follows in the film – all the death, carnage, mayhem and destruction of several historical landmarks – is officially All Peppe’s Fault.

Years of watching Godzilla and Gamera films have trained me to spot a Kenny from one county over, and Peppe’s got all the hallmarks. He’s really only missing a pair of Japanese school system-mandated short shorts, for which I thank Gia. Like all Kennys, Peppe is coded “cute” by the film – that precocious, arrogant, narcissistic breed of cute that sets my teeth permanently on edge. Were you or I to fish a strange canister out of the sea right after witnessing a spaceship crash, we might treat it with suspicion. Peppe’s first and only thoughts are of how best to profit from this discovery. This is, naturally, treated as a natural sign of youthful precociousness instead of a film-length indictment of Peppe’s dangerous irresponsibility. After all, this isn’t his film – Peppe isn’t a character, he’s a empty suit of clothes we’re supposed to be pouring ourselves into. And his own, sick breed of stereotype, rarely seen now, but thick on the ground in the late-50s: a genuine Western Fanboy.

So he sells the canister’s contents off to a vacationing zoologist, Dr. Leonardo (Frank Puglia ). Like his Japanese counterparts (who were already mainstays of television at this point, but wouldn’t fully conquer film until the late-60s), Peppe will get away with this Scott free. Thankfully, unlike the more famous Kennys, Peppe will be sent packing by the middle of the second act, saving us all his from his horrible child acting and grating, child voice. Still, his mere presence signals a shift in the genre and in the studio we’re dealing with here, Columbia. At this point in its life, Columbia faced a landscape leveled by the 1948 Supreme Court decision to break up the studio/theater monopolies that helped Hollywood have a Golden Age. 20 Million Miles to Earth is trying to appeal to everyone. There’s a kid for The Children to identify with and adults to laugh at, some Obligatory Romance for The Ladies, and manly military men fighting a monster for Dad (and the kids smart enough to hate Peppe, because he’s such a little shit).

This is fine for the bottom line, and 20 Million Miles has kilotons more bang for its bucks than, say, the despicable waste of everyone’s time that was The Deadly Mantis..But it’s obvious these writers had no idea what they were doing. Their script makes the critical error of dressing a bland story up in technobable and calling that “science fiction.” Peppe’s sole character trait – which, again, drives the entire plot of this picture – is an obsession with cowboys, especially with buying a hat from the “great country of Texas,” The kind “that they wear when they shoot the bandito” This shows what at least one of these writers wished he could’ve been working on. Obvious derivations from other, better sci-fi properties shows that no one else really had their heart in this…with the probable exception of Harryhausen. He got a vacation in Rome out of the deal, as did our main star, William Hooper. The rest of the cast had to act against rear projection backdrops (and it shows) or trudge through Sicily-as-played-by-Southern-California.

I’m not saying anyone deliberately ripped-off The Quatermass Xperiment or anything. Just that they totally ripped-off The Quatermass Xperiment‘s guy-brings-alien-back-in-spaceship conceit. That has a long and storied genre history in its own right, so it’s not like Nigel Kneale should get all the credit. But the next time you hear someone call this film “original” you will know that person has just come out as a fool.

The first half-hour’s spent patiently waiting out the cliché storm with only a few stereotypes for Odious Comic Relief. If one wanted to construct a spoof/parody of an American monster movie from the 50s, this would be a perfect template, a Zero Hour for your prospective Airplane. Keep watching and you’ll find yourself in the presence of a USAF-issued hero (as in Deadly Mantis) and his Love Interest, a Professional Woman who don’t get no respect on account of her doin’ a “man’s job” while in possession of lady-bits.

At least she doesn’t have the gender-ambiguous first name that would become its own cliche soon, like Dr. “Pat” from Them!. Here, her name is Marissa (Joan Taylor, another survivor of the Flying Saucer attack on Washington) and her meeting Our Hero at his hospital bedside is 20 Million Miles to Earth‘s version of a Meet Cute. I didn’t really find it all that cute until Our Hero, Colonel Calder (William Hooper) literally shakes his sole surviving shipmate to death in an attempt to wake the poor guy up (to what look like third degree burns – and not a Rangeveritz Technique in sight). Making things funnier, the poor guy’s named Dr. Charmin (Arthur Space). Yes, I can see the IMDb spells it “Sharman,” but I’ll still call my bad jokes valid thanks to similarity of pronunciation.

After squeezing Dr. Charmin, Col. Calder settles down and apologizes for being a dick…after Marissa shoots him up with sedatives. Despite just survived a spaceship crash, the motherfucker refuses to rest. He must find “the container” and its specimen.

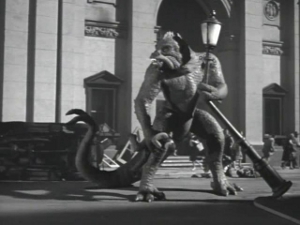

Unbeknownst to everyone, the specimen’s already hatched, birthing a chicken-sized, two legged, reptilian creature which goes unnamed in the film but which it’s creators named Ymir after a frost giant from Norse mythology. Ymir doubles in size overnight thanks to a curious over-reaction to Earth’s atmosphere, prompting Dr. Leonardo and Marissa to up stakes for Rome before the little fucker gets too big to fit in a proper lab. In a scene as excellently done as it is inevitable, Ymir grows too large for its cage and escapes into the Scilian countryside with Col. Calder and the military in hot pursuit. This (eventually) culminates in the creature’s spectacular capture in a farmhouse and its carting off to Rome, like a barbarian of old. Just as inevitably, it escapes, setting up the climactic rampage across the Seven Hills that’s the only part of this movie anyone remembers. For one thing, its creator specifically wanted to tap the same well King Kong taps into. For another, the ending’s totally spoiled by this movie’s trailer. Which, I can say with the full weight of truth, helped me learn to read.

It’s a perfectly straightforward trailer for an imperfectly straightforward movie. Apart from the acting problems (compounded by horrible accent problems) 20 Million Miles to Earth is terribly predictable if you’ve seen more than one giant monster movie from this period. Probably even if you haven’t. The Chick and Scientist archetypes are combined in a way fans of Them! should recognize (Marissa’s even saddled with an absent-minded Imminent Scientist father, just like Dr. Pat), while the Military, obviously, dispatches a whole unit into this movie. Far too many extraneous padding scenes are wrung from Col. Calder’s and his superior’s efforts to explain everything to the Italian government and get themselves some Ymir-hunting permits. I suppose it’s all time well spent since, by the end, the USAF is straight-up invading Rome, battling an extraterrestrial incursion at no extra cost to Italian tax payers! World Police! Fuck yeah!

The last half of this movie sticks in the mind because it’s scientifically designed to make any FX junkie happy they suffered through the first half. Slice the movie in two and we’d all be better for it. Fuck Peppe. Fuck children in general. I was a child once; I watched plenty of giant monster movies and I never once thought, “If only an insultingly simplified caricature of my age and gender demographic would show up, really make this movie complete!”

Maybe I’m being unfair – (“maybe?”) – Peppe’s another one of those plot devices that walks like a character. At least Calder and Marissa are archetypes, and their actors are adults who at least try to dump their exposition with conviction. Joan Taylor puts significantly more attitude into “Almost-a-Dr.” Leonardo than she put into “Mrs. Dr. Russell A. Marvin,” her last major sci-fi movie role. William Hooper was one of the least-awful things about The Deadly Mantis, a film that gave no one anything to do, apart from the Best Brains. Seeing Hooper doing something (a succession of somethings, no less) is heartening. The two don’t have much time to go from Antagonistic Doctor/Patient to Romantic Couple, but their limited time keeps the obligatory romance from being onerous. I suppose I should be happy it’s as underdeveloped as it is.

Because I know – you’re just here to see some kickass stop motion monster action. All I’m saying is, the “boring” parts of this movie aren’t as boring as they could be. Even Peppe kept me awake, spewing a constant stream of curses at the TV. And you’d best be awake, or you’ll miss the awesome action you came for. I don’t just mean the Ymir vs. Elephant fight, or the climactic Battle of Rome. For me, the stand-out scene comes when a man-sized Ymir attacks the farmer dumb enough to jab a pitchfork into its back (after Col. Calder’s explained to everyone that this breed of Venusian doesn’t attack unless provoked). In any low-budget movie (take a drink every time you see a rear-projected background), such top-notch effects work stands out, and this little bit of peasant-mauling’s certainly going to inform my readings of several Sinbad and Jason movies to come.

But for now, this is a movie where a farmer fights a reptile from Venus and for that, it’s certainly worth something. How much I leave to you, with the warning that you’ll probably have to be a fan of this particular strata of monster movie to even get to 20 Million Miles to Earth‘s so-called “good parts.” In a sadly apt metaphor for American monster movies in general, its great effects service a hackneyed, derivative story other movies did better half a decade beforehand. Is it any wonder America’s children embraced Japanese kaiju movies in the 1960s? Look what the domestic market had to offer them.

No, seriously, look at it. Fast-forward through the first forty minutes if you have to, because Harryhausen does great work in the final fifty. Hell, his work in the first thirty is arguably more impressive, since Our Monster has to interact with humans on a scale his Japanese cousins rarely stoop to. Ymir might not generate the King Kong-levels of pathos his creators were gunning for – too reptilian, no Love Interest, the score’s not nearly good enough, and his cries is a bit too nerve-damagingly high-pitched – but he is a great monster. His movie might’ve been great if anyone other than Harryhausen had actually cared about it, or thought of it as something more than a number on a balance sheet.

Maybe if they’d all received two weeks in Rome as part of their various deals…and by “they” I mean everyone, from Our Lovers to our gaffers. I can imagine Charles H. Schneer walking onto set one day and announcing, “Fuck it! That does it: obviously, Ray’s the only one here having any fun so…Roman vacations for everybody!” Now that’s what I call motivation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

When I was kid, and after watching quite a few monster movies, I worked out a formula for whether or not I thought a monster should be killed by the end of a movie.

Factor One was whether or not the monster was “bad” i.e. whether it actively went out of its way to kill people or if it primarily killed people because the people were fucking with it.

Factor Two had to do with size. The bigger a monster was, the more people it had to kill in order for me to feel like it should get killed in return.

Clearly my sympathies were with the monsters, especially the giant monsters. It’s a rare monster that’s both bad enough and kills enough people to justify it getting killed in return. Poor Ymir.

(I worked out the formula originally when I was trying to figure out why I felt bad that King Kong got killed but okay when Godzilla, in the original film, got skeletonized. New York would have been fine if Denham had just left Kong on the island. Kong “only” killed less than two dozen people during the course of the film. Godzilla on the other hand might have had some justification for his rampage (nuclear hangover?) but he slaughtered hundreds if not thousands of people. Even as a kid, who felt more sympathy for monsters than humans, I thought the world would be better without that Godzilla in it.)

I like that ethical calculus, despite some disagreement with its main assumption i.e., I never much cried when the monkey died, though my mom certainly did. As to Godzilla…

From a humanitarian perspective, I quite agree the world was much better off after Dr. Serizawa’s sacrifice. But from a fan perspective, it raises a couple of questions that always nagged me. Did the first Godzilla reconstitute himself sometime before Godzilla Raids Again? Or is the Godzilla we follow for the next fourteen films a different monster than the first? At least 1985 ignored the questions and Godzilla X Mechagodzilla answered them in as concrete a manner as possible.

I realize it comes down to picking your own favorite continuity, like any comic book, but man…every time I think about it, my head starts to swell.

Then again, every time I think about the time paradoxes that flow from Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, my head implodes and I have to do the mental version of CTL+ALT+DEL

I agree this movie isn’t as good as it should be, but one thing about Nathan Juran, the director. I knew one of his niece’s in college, and, at least according to his family, he really enjoyed effects films. He started out doing art direction (even won an Oscar for it) but he ended up directing a lot of monster movies and the like because he genuinely enjoyed the effects process. Now, that is not to say he was necessarily good at it, but he certainly wasn’t pining to be in higher prestige films.

Oh, one other thing: isn’t Pepe the Ur-Kenny?

I’ll have to re-watch The Black Scorpion now. Both of them.

BTW, that monster-comes-in-on-ship cliche goes all the way back to Dracula THE NOVEL.

(because that’s how diseases were spread–thru commerce)