Though he began life as a humble Godzilla rip-off in a land and time glutted with them, Gamera would come to symbolize everything that went so horribly wrong with the Golden Age of daikaiju cinema. But let us not tell sad stories about the death of kings just yet…like his more famous cousin/industrial competitor, Gamera began life as a serious apotheosis of the paranoia and insecurity of his age. But even here, at the beginning, we can see his creators at Daiei Studios sowing the seeds of their creation’s destruction.

Though he began life as a humble Godzilla rip-off in a land and time glutted with them, Gamera would come to symbolize everything that went so horribly wrong with the Golden Age of daikaiju cinema. But let us not tell sad stories about the death of kings just yet…like his more famous cousin/industrial competitor, Gamera began life as a serious apotheosis of the paranoia and insecurity of his age. But even here, at the beginning, we can see his creators at Daiei Studios sowing the seeds of their creation’s destruction.

And speaking of destruction…it’s 1965 again, and despite rising tensions between the Superpowers, someone’s still managed to scare up the funding for an Arctic expedition (chasing that fabled Northwest Passage, no less). As the film opens, the expedition’s official zoologist, Dr. Hidaka (Eiji Funakoshi), his typically hot assistant, Kyoke (Harumi Kiritachi), and your standard news hound, Aoyagi (Junichiro Yamashiko), stop by an Eskimo hut to warm up and quiz the natives. A formation of toy planes interrupts their welcome. “Russian planes,” Hidaka says.

The Americans react at once, shooting the uncommunicative invaders down. A “low-megaton atomic bomb” explodes on impact, while the rest of the planes retreat to Siberia. Hidaka and co. see the explosion, but somehow miss the giant, bipedal turtle that crawls out of the blast zone. This, a helpful old Eskimo dude tells them, is Gamera, “the devil’s envoy.” And he ain’t kidding. As he wastes everyone’s time explaining the plot, Gamera destroys the expedition ship, and our director, Noriaki Yuasa blatantly rips-off key shots of frantic wireless operators from Ishiro Honda’s Gojira. Outside, Gamera discovers the ability to spit fire through a nozzle improperly concealed in the back of his mouth. It must be the 60s! Excelsior!

The Americans react at once, shooting the uncommunicative invaders down. A “low-megaton atomic bomb” explodes on impact, while the rest of the planes retreat to Siberia. Hidaka and co. see the explosion, but somehow miss the giant, bipedal turtle that crawls out of the blast zone. This, a helpful old Eskimo dude tells them, is Gamera, “the devil’s envoy.” And he ain’t kidding. As he wastes everyone’s time explaining the plot, Gamera destroys the expedition ship, and our director, Noriaki Yuasa blatantly rips-off key shots of frantic wireless operators from Ishiro Honda’s Gojira. Outside, Gamera discovers the ability to spit fire through a nozzle improperly concealed in the back of his mouth. It must be the 60s! Excelsior!

In the Japanese cut of the film, Hidaka makes it back to civilization and tells everyone not to worry. His colleges are at least smart enough to expect Gamera to drop dead from radiation poisoning. Needless to say, everyone’s surprised as hell when Gamera shows up in Japan (of course) and starts smashin’ things… like Tokyo, with its thoughtless teenagers obsessively dancing the night away while a beach-blanket rock band plays. Will humanity survive? Really gonna have to strain our brains on that one.

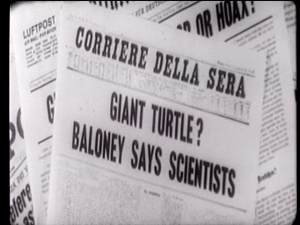

In the America cut of Gammera the Invincible, we see an entire cast of American actors portraying Air Force flacks, desperate to deal with what’s no doubt become the worst morning shift in history. And then there are these rumors of a giant turtle. Puh-leese! The American cut of the film (with its superfluous, titular “m”, directed by Sandy Howard) treats us to an collage of newspaper headlines (all in English), an establishing shot of New York, and a panel discussion on the “Gamera controversy” hosted by Mr. J.T. Standish (Thomas Stubblefield). Despite being a completely meaningless distracting from the main plot, I appreciate the black (and white) Cold War humor tinging this little aside. The sight of dueling “experts” became a TV stable back in the 50s, coming into its own as the technical sophistication of modern life increased and its social systems edged ever closer to the brink of Armageddon (or so it seemed to the suits). Both the “fo” (Alan Oppenheimer) and “again” (Mort Marshall) sides of the debate come across as melodramatic blowhards and, in the most realistic moment in the film, both wind up shouting at each other across Mr. Standish’s lap. (“Read, you ignorant ape!“)

In the America cut of Gammera the Invincible, we see an entire cast of American actors portraying Air Force flacks, desperate to deal with what’s no doubt become the worst morning shift in history. And then there are these rumors of a giant turtle. Puh-leese! The American cut of the film (with its superfluous, titular “m”, directed by Sandy Howard) treats us to an collage of newspaper headlines (all in English), an establishing shot of New York, and a panel discussion on the “Gamera controversy” hosted by Mr. J.T. Standish (Thomas Stubblefield). Despite being a completely meaningless distracting from the main plot, I appreciate the black (and white) Cold War humor tinging this little aside. The sight of dueling “experts” became a TV stable back in the 50s, coming into its own as the technical sophistication of modern life increased and its social systems edged ever closer to the brink of Armageddon (or so it seemed to the suits). Both the “fo” (Alan Oppenheimer) and “again” (Mort Marshall) sides of the debate come across as melodramatic blowhards and, in the most realistic moment in the film, both wind up shouting at each other across Mr. Standish’s lap. (“Read, you ignorant ape!“)

In either case, we have a nuclear explosion, a Monsters, a Scientist, a Reporter and Chick and a General (Dick O’Neil) all within the first ten minutes. That’s part of Gamera’s charm. His films may be goofy as all hell, but they swing for the fences and hit what they aim for…most of the time. This first truly self-conscious giant monster movie is a case in point, never missing a mark.

In any case, back in the main plot, UFO sightings are making everyone Watch the Skies! The American cut of the film takes time out for a meeting at the Pentagon, while Japanese audiences proceeded directly to the story of Toschio (Yoshiro Uchida, voiced on these shores by Billie Mae Richards). The son of a lighthouse keeper, Toschio is a little boy in love with turtles. So much so he captures and collects the little bastards. So much so, his teachers bitch about it to his father and sister, who (in true mid-century fashion) try and fail to bribe Toschio into kicking the habit. “You have to make friend with people,” his big sis insists, before sending him out to throw his latest “pet” back.

In any case, back in the main plot, UFO sightings are making everyone Watch the Skies! The American cut of the film takes time out for a meeting at the Pentagon, while Japanese audiences proceeded directly to the story of Toschio (Yoshiro Uchida, voiced on these shores by Billie Mae Richards). The son of a lighthouse keeper, Toschio is a little boy in love with turtles. So much so he captures and collects the little bastards. So much so, his teachers bitch about it to his father and sister, who (in true mid-century fashion) try and fail to bribe Toschio into kicking the habit. “You have to make friend with people,” his big sis insists, before sending him out to throw his latest “pet” back.

Where’s mom? Wherever Disney moms go, apparently. Heartbroken at having to chuck Bert into the sea, Toschio flops down and starts playing with a stick…somehow failing to notice the two hundred foot, lantern eyed, bipedal turtle that sneaks up behind him. Eager for a look-see, Toschio breaks away from dad and big sis (slippery as an eel, this one is) and climbs up dad’s lighthouse…just in time for Gamera to knock it down. But rather than drop the little bastard down his throat with a casual flick of the tongue, Gamera saves Toschio from the street-pizza’s demise with an outstretched paw and a not-nearly-harsh-enough set down, right at his dad’s feet.

This dooms us all, especially Gamera. Toschio regains consciousness convinced that Gamera is inherently “good,” despite the flaming mountains of evidence to the contrary. Toschio’ll spend the rest of the movie attempting to make Gamera converts of every Scientist, General, Reporter and Chick within earshot, failing miserably the whole thing. With this, Toschio adds most vile of all cards to the Giant Monster Movie Character Tarot Deck: The Kenny. So named because, whether through collusion or coincidence, characters of this type are almost always so named in American dubs of films like this. These annoying little tykes had their origin in Japanese superhero serials, palling around with Earth’s masked defenders. They possessed the incredible power to penetrate even the most secure Top Secret government site.

This dooms us all, especially Gamera. Toschio regains consciousness convinced that Gamera is inherently “good,” despite the flaming mountains of evidence to the contrary. Toschio’ll spend the rest of the movie attempting to make Gamera converts of every Scientist, General, Reporter and Chick within earshot, failing miserably the whole thing. With this, Toschio adds most vile of all cards to the Giant Monster Movie Character Tarot Deck: The Kenny. So named because, whether through collusion or coincidence, characters of this type are almost always so named in American dubs of films like this. These annoying little tykes had their origin in Japanese superhero serials, palling around with Earth’s masked defenders. They possessed the incredible power to penetrate even the most secure Top Secret government site.

We’ll meet plenty of Kennys on our journey through the daikaiju genre’s Golden Age (which stretched, roughly, from the 50s to the 70s). As the horrors of That Recent Unpleasantness with the Americans receded from memory and a new wave of mid-century optimism and can-do-it-ness swept through the formerly-decimated lands of the rising sun, adults stopped going to theaters and started turning their annoying spawn out into the streets instead. On both sides of the Pacific it became an age of, “Go watch a film – dad’s too pooped to give a shit about you after a hard day of sucking up to the bosses. And as for mom, she’s got wifely duties to attend…and you just better be grateful you have a mom in the first place. Not everybody’s so lucky, you turtle-loving little punk. Now get outta here – go see a monster movie.”

As audiences grew younger, the makers of daikaiju film did what filmmakers do best: they pandered. Godzilla’s transformation – from Harbinger of Nuclear Doom to Savior of Planet Earth – was the first, obvious sign of this. The re-construction of Gamera reconstruction – from Harbinger of Nuclear Doom to “a friend to all children, everywhere” – was another. As was the increasingly large number of kid-aged characters, endlessly rooting for whichever monster has the “good” role this week (and/or his name in the film’s title).

As audiences grew younger, the makers of daikaiju film did what filmmakers do best: they pandered. Godzilla’s transformation – from Harbinger of Nuclear Doom to Savior of Planet Earth – was the first, obvious sign of this. The re-construction of Gamera reconstruction – from Harbinger of Nuclear Doom to “a friend to all children, everywhere” – was another. As was the increasingly large number of kid-aged characters, endlessly rooting for whichever monster has the “good” role this week (and/or his name in the film’s title).

Question: did the Kenny begin life – here, in the person of Toschio – as a sick joke, perpetuated upon youthful audiences by an older, wiser bunch of creative types still haunted by memories of war? Did writer Nisan Takahashi (who’d go on to write all of Gamera’s Golden Age adventures) throw Toschio in as veiled dig on the generation of fans he saw rising in the theaters across Japan and around the world?

You’ll have plenty of time to contemplate such things if you’re watching the American cut of this film. Apart from that humorous clip from Crossfire, 1965 (described above) the re-shot sequences that pepper the film with American actors add nothing to it. They serve only to break up the moody energy of he main plot, grinding the film to a halt for…God help us…Pentagon meetings…and…Jesus wept…diplomatic conferences. It’s as if Sandy Frank wanted to preserve the mind-numbing tedium of Cold War politics for generations of giant monster movie fans. Thanks, Sandman. We’ll never get these minutes of our lives back, you know? You’ve stolen them from us.

You’ll have plenty of time to contemplate such things if you’re watching the American cut of this film. Apart from that humorous clip from Crossfire, 1965 (described above) the re-shot sequences that pepper the film with American actors add nothing to it. They serve only to break up the moody energy of he main plot, grinding the film to a halt for…God help us…Pentagon meetings…and…Jesus wept…diplomatic conferences. It’s as if Sandy Frank wanted to preserve the mind-numbing tedium of Cold War politics for generations of giant monster movie fans. Thanks, Sandman. We’ll never get these minutes of our lives back, you know? You’ve stolen them from us.

At Daikaiju Gamera maintains focus, and that energy I mentioned…a creepy fetish for apocalyptic destruction that had largely vanished from the genre when this film premiered. The cheap, black and white film stock adds to this, and helps our director cut in appropriate stock footage of smashed trains and burning cities. It also helps Gamera avoid looking his age. The various suits and mechanical heads that bring Gamera to life look much better in black and white. The most visually dynamic monster to come out of Japan until Ultrama’s villains blew that curve all to hell, Gamera is either the coolest, or the silliest, city-smashing monster of them all, depending on your mood and the film you’re viewing.

This first Gamera flick is decidedly middle of the road, made for an audience that abandoned the genre en masse once the the glass teat, television, ensnared them. Strange as it may Seem, Gamera was among the last serious daikaiju films of the ’60s…which just goes to show you how weird things truly became. For more on that, see the following year’s Gamera vs. Barugon.

Daikaiju Gamera

![]()

![]()

![]()

Gammera the Invincible

![]()

![]()