had a lot on its shoulders, as evidenced by the ubiquitous banner headline every trailer, poster and DVD box still sport. “From the Visionary Director of The Sixth Sense,” it said, before adding “M. Night Shyamalan” almost as an afterthought, since no one really knew how to pronounce his name correctly in the Year 2000.

Fewer still knew that Sixth Sense was Shyamalan’s third film, the penultimate flick in his autobiographical period. All artists go through one, especially since its propagandists managed to make the dictum, “Write what you know,” synonymous with common sense. They forgot to add the necessary corollary: “The more you learn, the more you’ll be able to write about.”

Night’s first film, Praying With Anger, was about coming to terms with his heritage as an Indian kid raised in Philadelphia, watching baseball and eating hotdogs. Wake the Dead was about growing up Catholic, and going to school with the penguins in true Blues Brother’s style (though not nearly as awesome). The Sixth Sense was about Night’s childhood as a great big scaredy-pants wimp, afraid of Stephen King’s old bogey, The Thing Behind The Closed Door. Shyamalan just painted the doorknob red.

Unbreakable, then, is about growing up believing (no: knowing for a fact) that your dad is a superhero. The now-obligatory Shyamalan Child Character, Joseph Dunn (Spencer Treat Clark), is just as much of an authorial cipher as Sixth Sense‘s Cole Sear. Joseph’s emotional journey throughout the film also handily parallels the journey any comic book nerd goes through while watching it for the first time.

This is true for first-time and subsequent viewings, despite the equally-Obligatory Twist Ending. Which does for Unbreakable exactly what it did for Sixth Sense, altering the meaning of the film that preceded it in a way that deepens the experience by adding new dimensions.

The first time through, you think Unbreakable‘s a superhero mystery, with the mystery being, “Is David Dunn the hero Elijah Price believes him to be?” A second viewing shows the film is actually two stories, both asking the same questions about what superheroism is, what are its costs and consequences, and what place it might have in a world that more-or-less resembles our own (more so than, say, either mainstream comic book universe).

Again, this is only remarkable film-making in an age of commercial hackery like ours, but that doesn’t make it any less competent or worthy of praise. Night’s as much a comic book nerd as any of us, or he wouldn’t have paid so much attention to Joseph in the first place. And he obviously loved Watchmen, since this movie asks the same questions about which awful means justify which heroic ends. How many people would you kill to discover your place in the world? How many people have to die before heroic individuals step up, out of their boring, normal lives, and into the dark?

Elijah Price is a man born with osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic disorder that makes his skeleton very brittle. “I’ve had fifty-four breaks in my lifetime,” he says, “and I have the tamest version of this disorder.” A life spent in the hospital reading comic books leads Elijah to believe that, somewhere in this world, someone on the opposite end of his genetic curve must exist. A person that doesn’t get sick, whose bones are especially dense; someone who might be the latest in a long line of inspirations for those heroic stories that, eventually, inspired modern superheroes. “Someone put here to protect the rest of us.”

Or so Elijah explains to our actual protagonist, David Dunn (Bruce Willis) a security guard at the University of Philadelphia’s Franklin Field. Who, immediately after the credits, becomes the sole survivor of a spectacular train crash that claims the lives of all 131 of his fellow passengers. A note under the windshield wiper of his car leads David to Elijah’s comic book art gallery, Limited Edition, and Elijah’s theory about David’s place in the world.

All his life, David Dunn’s carried around the unbearable sadness common to all those who aren’t doing what they know (in their bones, say) they should be doing. “You know what the scariest thing is?” Elijah asks David, and thus us. (Perhaps Shyamalan’s preemptively answering those critics who expected another Sixth Sense, if only so they could complain about Night’s lack of originality.) “Not knowing your place in this world.”

It develops that David gave up a promising career in college football to marry his wife, Audrey (Robin Wright), a physical therapist who despised, not the sport (Night’s sure to underline that for us), but the inevitable injuries it causes everyone involved…except David, of course. David never got injured…until one midnight car wreck provided him with the excuse to quit football and settle into the married life.

A married life that, by the film’s present, is falling apart due to David’s ennui. Hence the job interview in New York, and the fateful train ride it necessitated. Hence the fact Audrey and David begin the film living in separate rooms on separate levels of their shared house. Joseph’s obviously the mortar holding this house together, and obviously well aware of his family’s dysfunctional dynamics. When Audrey and Joseph pick David up from the hospital (framed by the envious looks of the other 131 passenger’s grieving families) Joseph links his parents hands together. The camera follows those hands as Joseph turns away and both adult Dunns let go.

This is Shyamalan’s peculiar talent: a Hitchcockian ability to cram his frames full of characterization. You might not catch it all, but your brain does, and it makes second viewings of these early Shyamalan “thrillers” a special treat for those with sharp eyes. We first meet David on the train as the camera ping-pongs back and forth between him and the hot young sport’s agent who sits down beside him. We see David remove his wedding ring and instinctively know what his deal is. His awkward, fumbling attempts to put the moves on his seat-mate expose him for a socially inept dude left high and dry after temporarily thinking with his dick. Then, just to put a cherry on this shit sundae, the Jerry MaQuire refugee announces that she’s married – so married, in fact, she can’t even stand to sit next to we mere mortals. Watching her go, even more dejected than when he began, David looks out the window and puts his wedding ring back on.

Throughout, we watch other trains go by on the track outside David’s window (to the extreme right of frame). Two trains whiz by while he tries to mac on Married Girl, letting us know that there is, in fact, a set of tracks over there. We and the camera both are distracted by David’s failed pass – so much so that we don’t notice David’s train switched tracks until the moment he does. You can see the realization dawning as he stops staring out the window and starts to actually see what’s in front of his face. Hey, weren’t those trees over there a second ago? Pan out to reveal the rest of the passengers noticed this sudden track-change too. The shrill braying of their train’s whistle rises higher and higher as we cut to a full-frame shot of David’s face, outlined in white. A thick, grinding noise that (on a set of theater-grade speakers in the year 2000) sounded like Godzilla clearing his throat wipes out the soundtrack and…

Jump cut to: Joseph Dunn, catching the results of the (off-screen) train crash on the Plot Specific News Network. Where other filmmakers might’ve wasted fifteen minutes and millions of dollars on some ginormous crash sequence, Shyamalan’s much more interested in frying the fish on hand. The big one here – in a startling move that startled those of us who didn’t fall at The Sixth Sense’s fee – is a melodrama about another Everyman, his mid-life crisis, and the supernatural shit that finally motivates him to get off his ass and solve it.

It’s the film Shyamalan and his handlers marketed when they first sold us The Sixth Sense. That’s why that Twist worked so well. We went in thinking that would be a Bruce Willis movie through and through, only to be pleasantly surprised when we discovered the film’s true title should’ve been The Haley Joel Osment Show. In Unbreakable, Willis and his distant wife can actively communicate without the need for a pint-sized medium or one or the other being asleep. My third favorite scene in the film comes when we observe the Dunn’s first honest-to-God date in years (perhaps since before Joseph’s birth…?) through one, long shot that slowly zooms in on our slightly-happier-than-when-they-started-the-film couple. The two begin by playing the usual get-to-know-you games (the whole “what’s-your-favorite-x?” jazz) before Audrey wins with the $10,000 question: “When did you first know things weren’t working out between us?”

“I had a nightmare and I didn’t wake you up to tell me it was okay.”

Jesus Christ, fellow-David. Co-dependent much?

Yet, by focusing on this man and his family melodrama, Shyamalan grounds what would otherwise be a grand-but-didactic documentary on the place heroic archetypes have (or don’t have) in modern America at the turn of the Willennium. Sixth Sense used the same focus trick to lull us into a false sense of familiarity (Oh, we thought, watching the film for the first time, So Bruce Willis is gonna get with Haley Joel’s mom in the end and everything’ll be wine and roses for little Mr. “I See Dead People.”) before upending all assumptions in its last few acts.

Unbreakable, by contrast, deploys a purposefully traditional familiarity, because Shyamalan (like all comic book geeks of the time) was hyper aware that, without a thorough grounding in the mundane everyday, no one was going to take his superhero movie seriously. Then Touchstone sold it – not as the Contemporary Realist superhero movie it’s designed to be – but as a psychological thriller…whatever that means. For me, “psychological thriller” meant this trailer:

which showcases scenes and lines even further removed from appropriate context than most predigested trailer bits. That whole, “You don’t have a scratch on you,” bit only works as a proper punch line when it’s set up by the previous scene (where Joseph discovers the train wreck on PSNN).

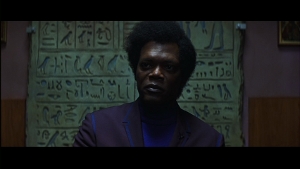

We don’t “discover” we’re inside a superhero film until we meet Elijah Price in his adult, Samuel L. Jackson form: an intense, driven man who made his hobby his profession. A tragic figure who survived a life of Body Horror thanks to his belief in the underlying order of the world. An order that casts him as the Arch Enemy to David’s Hero, leaving Elijah no choice but to assume the role he’s destined for, if only in his own mind.

Taking the Watchmen comparison to its obvious conclusion, Elijah’s an Adrian Veidt figure if every I saw one: an intelligent individual with personal traumas riding high on his shoulder, channeling his sublimated anger at the myriad failings of the modern world into (what he believes are) socially beneficial ends…involving mass murder.

But we don’t learn that until the end (or until we read some asshole movie critic’s over-long and self-indulgent “examination” of this flick). For most of the film, Elijah serves as David’s mentor, educating him in the world of superheroics, despite David’s frequent refusals of the Call To Adventure. For about fifteen minutes, Unbreakable plays with the notion that maybe David’s right and Elijah’s just a crazy man. As Audrey says after Elijah seeks her out at work and explains his theory to her (delivering the film’s best lines: “These are mediocre times, Mrs. Dunn. People are starting to lose hope. It’s hard for many people to believe that there are extraordinary things inside themselves, as well as others.”), “When people get sick for a long time, they start to think things that aren’t true.”

But we don’t really believe that, and the film doesn’t either. That’s why David makes the otherwise-inexplicable decision to bring Joseph along to Limited Edition. The two male Dunns meet Elijah for the first time together, and as he explains his worldview to them, Shyamalan fills the frame with their reactions:

I (probably too frequently) joke about certain shots from certain movies being representative of the prevailing audience reaction to said movies. But this time, guys…no foolin’. I’m super cereal. David Dunn represents the “general audience” reaction to this film: stony incomprehension, quickly followed by stoic acceptance that this whole story is some con artist’s bullshit line. But comic book fans? We were over there on the left of frame, firmly in Joseph Dunn’s shoes. He and I listened to Elijah Price’s line with the same expressions on our faces: awed wonder as we realized what we really had on our hands.

Then we see David at work, milling about the crowd at Franklin Stadium. We see him receive psychic flashes through physical contact with members of the public and know in our heart of hearts that he’s the Hero Elijah’s been waiting for. The rest of the movie is, like so many origin stories, us – the audience – waiting for the Hero to catch up.

But I don’t mind, because this origin takes its time, allowing us to both know and like each of the four major characters involved. Despite lavishing most of his attention on Willis and Jackson, Shyamalan’s sure to give Robin Wright (then Penn) and Spencer Treat Clark opportunity to shine. Audrey may be the Designated Skeptic but, out of everyone in the Dunn household, she’s the one who decides to finally patch their marriage up.

And as punny as it might sound, Spencer Treat Clark is a treat. Goddamnit, I hate kids and I hate kid-actors, but I love this kid because in him I see my twelve-year-old self. He and Willis sell the Dunn family to us with their affable on-screen chemistry. Without their frequent interaction (since David and Audrey’s getting back together functions as our major B Story) this movie would have a void at its heart, but thanks to the two of them, and their easy, nuanced performances as father and son, we can believe in the Dunns instead of just believing in the film they’re in. It’s the little things. Like this exchange:

Joseph (who’s trying to convince David to join a flag football game in the park): “I told them you were great!”

David: “Why would you do that?”

Or this, during the workout scene:

David (before attempting to bench press something north of three hundred fifty pounds): “You should never do anything like this. You know that right?”

Joseph: “Uh-huh.”

David: “Whadda you do if something bad happens?”

Joseph: “Get mom.”

David (looking at the barbell like he’s staring death in the face – which, if he were any other man, he would be): “…Right.”

Fuck yeah. Parenting, bitches. Try it yourself sometime…though, even then, things might not always work out for the best. As we see in my absolute, no-holds-barred, 100% favorite scene: when, in order to prove Elijah’s story to his parents (and himself, probably), Joseph steals dad’s service pistol out of the top shelf of the closet, loads it with bullets from the Rookie of the Year trophy, and threatens to shoot his father.

Unbreakable‘s the movie X-Men promised (and ultimately failed) to be the month before: a superhero movie that took itself seriously. That didn’t toss three thousand years of storytelling conventions in the gutter just because its protagonists are a bit outside the physical norm. That didn’t treat its characters like action figure models, or walking one-liner machines. A film with confidence in itself, that wasn’t afraid to strike out beyond the bounds of established comics and build a universe all its own.

In fact, Unbreakable did such a good job, its fans have been begging for someone to come along and ruin things for years by making a sequel. Things are far from perfect as it stands. The reason for that goes all the way back to Unbreakable‘s conception as a feature length first act.

There are several plot contrivances built into the narrative in order to draw out that first act, including all the elements of mystery that the film pretty much abandons by the end. Who, after all, could go five years without taking a sick day? Or anyone in their lives noticing they’d never taken one? Whether you got sick or not, the people around you certainly would, forcing you to take care of them. Sooner or later, one of them would probably notice that you’re always the Designated Caretaker. Over the years, your immune system’s innate superiority would only become more obvious, especially after your kid started taking daily trips into that greatest of viral incubators, public school.

Then there are David’s conveniently-“repressed” memories that function as mini-plot twists, attempting to string along all the attention-deprived douche bags who wound up calling this film “too slow” anyway. (Frankly, I think they’re all projecting.) There are two big ones that strain my credibility.

First, we’re meant to believe David repressed his memories of the incident where he almost drowned as a child. Joseph’s school nurse has to prompt him, going on to say he’s become a cautionary tale the students still whisper about around the pool, “like some kind of ghost story.” (“Did you hear about the kid who almost drowned in that pool this one time?”) Either no one told Joseph that story (which can’t be true, since he recognizes his father’s reference to it), or he never repeated it around the dinner table.

We’re meant to believe David’s memories of the car crash are equally shrouded. I could buy someone repressing their childhood near-death experience but…okay. You’re a college football god. You roll your car, survive uninjured and, in order to free your sweetheart, rip the passenger door out of its frame. By hand. Remember the vivid story of that awed accident survivor in Bill Bixby’s Incredible Hulk TV movie? The one who held up a burning car in order to save her son? Yeah. Something like that tends to stick in your head, even after the adrenaline wears off. I, for one, might even brag about the incident to my friends after my sweetheart woke up with nothing worse than a busted leg. Not like David had a concussion to deal with or anything.

And now that I think about it, how the hell did David fake his injury? Did he take a correspondence course from Clark Kent? “How to Pass for Normal in Five Easy Lessons; Glasses Optional.” Did the pressure of constantly faking it just build up and up and up, until it swallowed David’s memories of that night? And all the other times he might’ve discovered, over the course of his life, that he actually lives in a world made out of cardboard? One too-strong handshake is all it would really take…

But these are nits, picked during my usual multiplicity of pre-review viewings, all but invisible to less-analytic comic book fans than I. They’ll shoot completely over the heads of so-called “normal” people, and shouldn’t effect their reactions to this film at all. Shyamalan deploys all his suspense-enhancing tricks (especially the long, one-take shot) to draw you into this world. That first time I discovered this was a superhero world, it felt like a pleasant surprise. Nowadays, after years of watching superhero movies try and fail to do what this movie does so well, it feels like a revelation.

Plenty of superhero movies in this, the form’s Silver Age, attempt to be “grim,” “gritty,” “realist” or whatever term people use for “like a comic book from the early-90s, when comics still sold well.” Most fail, because they all lack the courage to do what Unbreakable did: take time, establish recognizably human characters, and tell a well-constructed story about them.

I know, right? What a twist.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Enjoyed this review, seen Unbreakable many times but never picked up on some of the things you did. Good comparison to Shyamalan’s Hitchcockian use of shots to provide characterization. You probably didn’t feel you needed to include this because it’s been talked about so many time but I think his use of reflections in Sam’s characters scenes were pretty brilliant.

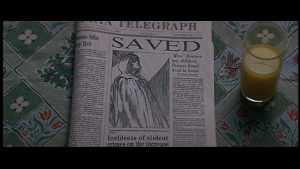

I felt the need, but couldn’t find a proper place to stick those observations with out mucking up the review’s flow. It’s another one of those hidden visual rewards Shyamalan threw in for those of us who watched this twice. The “reflection” motif haunts both of our protagonists, for reasons that become obvious by the end. Also couldn’t find a place to talk about our characters contrasting color palettes. Obviously, Elijah’s purple and David’s green, but eventually the reflection motif comes in again, with Elijah’s story moving from warm colors (in a past full of yellows, bright browns and brighter purples) to cool (in Limited Edition, which is one great big, blue bummer) even as David moves from the cool, blue world of the train to a lighter, brighter world of orange juice and familial happiness. Just another one of those things, invigorating a narrative we’ve (literally, in my case) seen a thousand times before.

Ah, M. Night’s last good movie. Really dug this back when it came out, and it seemed like comic book movies might not become so cookie cutter (Ang Lee’s Hulk furthered that impression).

Indeed it did. So much so that, at the time, I looked into the future with horrified anticipation of a million and a half hacks shamelessly copy-pasting Shyamalan’s use of the Long First Act, or Lee’s “turn your frame into a collage” aesthetic sense. In a weird way, I’m kinda glad neither of those films did well enough to be the influential mega-successes they really deserve to be. Instead, they slunk away after earning slightly less money than Hollywood’s One True God, the Excel Spreadsheet, projected. This left Spider-Man free to more or less define the genre and gave me my best excuse to call this “the Silver Age of superhero movies.”

I can’t imagine either of these would yield very good formulas, even if they had been mega hits. I dug this more than Lee’s The Hulk, though I liked both.

Same here. Hulk had fifty years of baggage to tote around (as its plot line clearly shows) while this came to us with no preconceptions besides the genre ones, which it incorporated into and commented upon through its narrative, assimilating the over-analytical fanboy position for its own. No, it says, I’m on your side. And since I’m an original production, you know I’m not lying, and I’m certainly not trying to sell your kids toys. Whereas all the franchise superhero shows have to serve at least two masters: their corporate overlords, and the fan base that supports them. In that order (unfortunately)…most of the time.

Pretty much hit the nail on the head, as usual, Mr. DeMoss. Is anyone doing much genre film these days with any kind of personal imprint, at least that makes it to theaters? I’m so out of touch these days.

Shit, man, that’s the twenty million dollar question. One I can’t really answer with any certainty anymore now that even the reliable staples of the Film School Generation have kicked themselves upstairs and pretty much given up trying (or let their padawans rip them off with their blessing – see also, Abrams, J.J. and Spielberg, Steven; collaborations between). Hell, I’m the guy who loved Kick-Ass more than either of the Iron Man films, so it’s not like I’m plugged into some Great Zeitgeist.

God I love this movie. It’s one of the few movies that I refuse to watch often because they’re something special, the ones I don’t want to ruin through familiarity. Unbreakable, Big Fish, Edward Scissorhands, Alien, all these movies I don’t want to be able to quote from, instead just being enthralled by them.

I really enjoy M. Night’s use of the long, quiet shot, Hitchcockian as you say, where tension is built just by the interaction between characters. I remember watching this in the theater and being sure (sure!) that the orange juice, constantly on the breakfast table, had something to do with the greater plot, just because it had so much presence. The whole damn movie has that much presence.

Nice review, by the way.

Thanks, Steward. Nice comment, straight away. I can understand and sympathize with the refusal to watch a film, lest over-familiarity ruin the experience. That’s happened to me several times, with several films, over the years. And someday I’ll organize them all into their own theme month.

Ugh, this one. I should really like it, but honestly, I think M. was drunk when he blocked out half of the shots. The one where Bruce and Sam L. are talking outside the stadium and they’re almost completely out of frame especially, it just broke any kind of immersion that I had previously. The story is kinda meh IMHO, fresh for superhero movies but kinda a sci fi trope generally. The acting, now, he got some damn fine performances out of everyone involved.

“Meh” is a pretty accurate way to describe a two hour first act, actually. I see where you’re coming from, even if I don’t live there. That’s what ruins most prequels. But, yes, what a difference good acting makes. Like so much else, Young M. Night had one hell of an eye for casting. One of the many reasons I don’t think he started hitting the bottle in earnest until Signs.

I enjoyed this film especially for the ridiculous idea of samuel l jackson in a wheel chair – not the kickass that he usually portrays and the not so dysfunctional, dysfunctional family saved (of course) by the woman. And your review was spot-on right, and way deeper than I normally go when I watch a film. Keep opening my eyes to the world behind the mindless consumption of conventional culture – or what passes for art these days – am not too old to learn.

No one is. I will, as always, do my best to plumb these depths.

“If you look at his career backwards, he starts as a hack filmmaker who learns how to write characters and eventually shows some promise.”

That’s something…if you look at Michael Bay’s career backwards, he’s a hack destroyer of beloved childhood franchises who sheds his pretensions of being Roland Emmerich and revives the Buddy Cop sub-genre just when the Lethal Weapon franchise was getting old.

Look backward, Roland Emmerich ceases to piss all over Shakespeare’s grave and makes a series of Disaster movies that actually increase in quality, before abandoning the genre to tackle Big Idea sci-fi in the most cliched way possible.

Damn, this is too much fun…