Things may be different in Japan, but over here in the USA only a bare handful of superheroes were born in movieland. Most come out of comic books, something that astonished me back in 1990 and still astonishes today. You’d think superheroes and the motion picture would go together like peanut butter and a consenting adult sexual partner. Thankfully, over the years, a good crop of people have shared this view and worked their butts off to make their “original” superhero productions happen.

One of those people is Sam Raimi. After the success of Evil Dead 2 proved people couldn’t get enough of Raimi’s morbid, slapstick “humorror,” he could’ve sat back on his laurels and made Army of Darkness. Hell, he could’ve reshot the same story (again), called it Evil Dead 3: The Dead Shall Rise and people would’ve loved him for it. Some of us expected just that from Army of Darkness, in fact.

Instead, Raimi went for the moon and tried to catch the Batman train, already steaming through Hollywood in the summer of 1987. No dice. He tried to get a Shadow movie made, but no one wanted to take a chance on some period piece starring a character from radio dramas. Believe it or not, Raimi even tried to get a Thor movie off the ground during this period. We never got anything out of it, but Raimi struck up a friendship with Stan Lee that would come in pretty damn handy (for both of them) about twelve years down the road…

But by 1988, no one really trusted Sam the Man. Sure, he made a couple of horror films but, once Batman fever swept the nation, every big name superhero property suddenly needed a Big Name Director to survive the industrial shark tank. Raimi just wasn’t big enough at the time. So he did the sensible thing and said, “Screw the comic book companies and the studios, too.” Except Universal, the old gray lady of American Horror Film. They decided to be cool and, in a fit of madness, handed Raimi sixteen million dollars and said, “Go for it, kid.”

It was every nerd’s dream come true and I think that goes a long way towards explaining the manic energy of Darkman. This is not a perfect film, though it is the Perfect Superhero Film of its Day. Even with $16 million, it strains against its budget and comes off looking rather cheap in spots. But I don’t care. I love this flick, and I love Sam Raimi for making it.

He and I have the same sense of humor. How do I know? Because I know he and I watched the same films as children. All I have to do to know that is watch Darkman. I can see it, the same way Frank Black can see into the minds of murderers. I knew, from the moment I first saw the trailer on an old VHS tape of Tremors, that Sam Raimi and I were on the same, glorious page:

How could I not see something like that?

Right off I learned Raimi and I both watched a lot of bad television, because he gives us a pre-credit sequence. As in Evil Dead, we meet the villain of the piece before we meet the hero…so meet Robert G. Durant (Larry Drake), a gangster who dresses like the 1940s will never go out of style. In fact, all Durant’s men are substantially more dapper than their competitors for the decaying waterfront property of this City (actually L.A., though the way Raimi shoots it, L.A. becomes something of an Every City). I guess that’s why Durant’s men get to take down a warehouse full of thugs with no casualties, despite being purposefully herded into the middle of the room.

Oh, but one of their number (Dan Hicks) has a machine gun built into this wooden leg. There’s a secret weapon to fit tip the scales of battle. Just to prove his Villain Cred, Durant unveils his creepy fetish for chopping off people’s fingers with his cigar cutter. Seriously, can you imagine what watching this did to little five-year-old, me? Well, you’re looking at it.

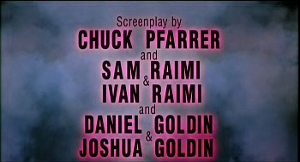

Then the credits, visually glorious though they may be, showcase Darkman‘s two major problems. For one, it wears its inspirations on its chest, smack dab in the middle of a yellow pentagon. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Danny Motherfucking Elfman’s score. And I love this score. I even own a physical copy of it. For a long time, it was my go-to incidental background music. Yet even I recognize it for the derivative, over-cooked mess that it is, trying to be twelve different things at once, doing none of them more than half-well. Take a gander at the screenplay credits and see if you can guess why that is.

First we see Chuck Pfarrer, the guy who wrote Navy S.E.A.L.S., who’d go on to write Hard Target, Virus and…God help us…Barb Wire…. We can thank him for Durant’s trophy collecting habits and the years of nightmares they’ve engendered since this movie’s release. Then we have the director and his brother, Ivan, the doctor in Raimi’s family, who worked on drafts two through four together, trying to get the Science in this flick “right”…yeah, we’ll see how well that worked out. Then we have the Golden Brothers, who were hired by the studio to doctor things up…and I’ve never heard of either one of them again.

Ordinarily, this many cooks in the kitchen would spell a film’s ultimate doom. But this is Darkman. It stands in the face of the my critical gaze and resolutely gives me the finger. It has me by the balls from frame one, knows it, and isn’t afraid to occasionally squeeze just to make sure I’m still paying attention.

That’s because Sam Raimi and I both grew up reading bunches and bunches of comics. His camera has so much energy it powers you over the clunky exposition, past the two-dimensional characters, and into the best damn superhero tragedy ever committed to film.

So meet Dr. Payton Westlake (Liam Neeson!), a brilliant Scientist…of undetermined discipline, qualifying him for the capital-S. Together with his lab assistant Yakitito (Nelson Mashita), Dr. Westlake’s on the verge of perfecting a synthetic skin he’s created for use in grafts and such. You know. Like the kind burn victims need in bulk. Sure would beat the hell out of ripping skin off their calves and stapling that onto someone’s arm…chest…face. But going into a line of research like that, and for such altruistic reasons, is just asking for some dramatically ironic consequence to befall you.

Here’s this guy, this Scientist, all he wants to do is help disfigured people avoid the finger pointing and gossipy whispers of the easily-startled Norms. Even better, Peyton’s so brilliant he’s put generations of Frankensteins to shame and actually created life with his vats of multi-colored chemicals. His fake skin’s so good it has its own cell structure. We know because we get to watch it fall apart under the microscope. Liam Neeson instantly communicates Petyon’s frustration at what (we infer) is the latest in a long line of failed experiments with one all-encompassing word: “Shit.”

See, the skin is photosensitive. After ninety-nine minutes (on the dot, always, without fail) in normal light it melts back into a bubbly puddle. Hence Peyton’s cursing. Hence the irony™ to come. But before that, we get our tragedy on by finding out, not only is Peyton a Brilliant Scientist© with his own Seth Brundle loft/lab, he’s also got a hot lawyer girlfriend named Julie (Frances McDormand). Sure, she’s a Strong Professional Woman stereotype but the two act so natural together in their one tranquil, domestic scene that I’m reminded of some my own previous relationships. We synchronized our drinking, too.

Actually, that’s a damned uncomfortable thought considering what follows…

First, Peyton asks Julie to marry him…but since he’s such an awkward nerd with such horrific timing and an abysmal lack of what modern relationship scholars call “game” even his best line sounds like a bad joke:

“All marriage means is if you answer the phone in the morning and it’s my grandmother you don’t have to pretend it’s the wrong number. Poor woman’s beginning to think she has Alzheimer’s.”

God bless a world before cell phones. At least Julie laughs. But even with a stellar pitch like that, Peyton fails to get a straight answer out of his gal. “I’ve gotta think about it,” she says, obviously busy with the whole “I’ve uncovered a corruption scandal reaching to the heights of civic government” thing.

Now pay attention because this will have nothing to do with the rest of the plot: a developer named Lewis Strack (Colin Friels) bribed someone on the zoning commission because he wants to buy up a shitload of waterfront land and turn it all into skyscrapers… like we’re in Singapore or something. Fortunately, the zoning board member was stupid enough to write all this down in a memo. Unfortunately, Strack can’t help acting like a creepy douche when Julie confronts him, not even trying to deny her allegations. Strack insists that it’s all part of getting the job done, building the future. He further suggests Julie visit the can and allow him time to remove any evidence of his shady dealings from her brief case. Thank God she didn’t bring it with her.

No, she left it at Petyon’s place. Good one, Jules.

I kid our Obligatory Love Interest. She actually starts the film off quite strong. Her intimately awkward interactions with Peyton do exactly what they need to do: humanizing both of them, even as the movie pretends to ignore him completely. It’s almost a shame the script shoves Julie aside since, up until this point, she’s been quite the kick ass character. But ten minutes is enough time with a strong, female protagonist for this flim. Time to focus on Movie B, The One That’s Actually About Darkman.

So Movie B begins when Durant and his Insane Clown Posse run up on Peyton’s lab, killing Yakkitito (bye, Yakki! – sorry you won’t be mentioned again anywhere…except for one throwaway line in a tie-in novel two years later) and torturing Peyton at length when he claims ignorance of the memo they’re looking for. It was a painful scene to watch at age five and it’s even moreso now, the entire sequence being not one damn bit funny. Reminding us all that this is still the man who gave us Evil Dead 1…which wasn’t funny either. It was gross and unnerving because it was so cruel. It reveled in its cruelty…or, at the very least, the Dead did. So does Durant, and thanks to Larry Drake’s manly jowls, what would’ve been a one-note villain becomes an icon of amoral psychopathology.

And thanks to Raimi’s eye we know that, no matter what, Durant and his crew are going to get what they deserve. We need to see their violence against Peyton the same way we needed to see the destruction of Officer Alex Murphy, Detroit Police Department. Like Paul Verhoeven, Raimi uses that old grindhouse trick of shocking us with violence towards the hero at the beginning, justifying the hero’s subsequent, violent revenge. Like Verhoeven, Raimi meant to get us talking about vengeance, justice and the fine line between the two…especially when you become a vigilante superhero after a group of gangsters blow up your house.

But whereas Robocop is Lawful Good to his core programing, Dr. Peyton Westlake wakes from his lab explosion firmly on the side of Chaos. The fact that he survived in one piece is a miracle of probability. The fact that he survived, got fished out of the river, and brought to the hospital as a John Doe, is downright insane. As “luck” would have it, Peyton also happens to live in a universe that’s perfected the Rangeveritz Technique. The what, now? I’ll let Dr. Exposition explain the “science” Raimi and his brother worked so hard to get “right” (har-dee-har-dee-har):

“Quite simply, we sever the nerves along the spinifulanic track, here. Which, as you know, transmits impulses of pain and vibratory sense to the brain. No longer receiving impulses of pain, you stick him with a pin…and he can’t even feel it.”

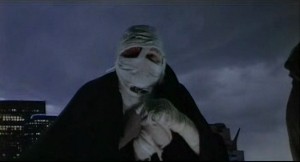

Unfortunately, the human brain has a bad habit of flooding itself with chemicals to make up for the loss of tactile stimuli. This leaves Rangeveritz patients suffering violent, uncontrollable mood swings, compounded by whatever depression they might feel after waking up without a face. By Contrived Movie Law, this also “gifts” Petyon with adrenaline-fueled super strength. Breaking his restraints, he escapes into the night, a nameless hobo dressed in bandages and a great coat fished from a dumpster.

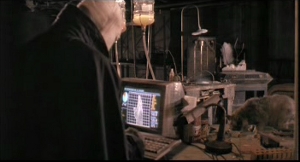

Finding his lab a burnt-out shell, Peyton reconstructs it in an old factory, becoming a resident of the real estate everyone’s arguing over…for some reason. With tables made from shopping carts, a stray cat for a roommate, pirated electricity and a press powered by a pull-cord (let’s hear it for Science!) Peyton spends the rest of the film enacting a one man guerrilla war on Durant, Durant’s Posse, and Durant’s ultimate boss…even as he stupidly attempts to get back together with Julie…without telling her about the whole “burned beyond recognition” thing.

Darkman’s real hook (apart from making the black longcoat the cape of our age) is his ability to look like anyone, quite apart from the rage-fueled super strength (which the film tends to conflate with invulnerability anyway) and complete ignorance of pain. Never mind his ability to walk around with only 60% of his original skin and not drop dead from a massive infection – this man’s a Scientist (as he attempts to remind himself whenever the mood swings strike). Thanks to that, and his computer’s processor power, he can shape his artificial skin to any form. It even works off scanned photographs, like the kind he takes of Durant and his gangsters while stalking them from the safety of garbage strewn alleys.

The film gets a lot of mileage out of this gag, with other actors portraying Darkman even as he portrays them. There’s a sequence where Peyton poses as Durant and robs a convenience store (that’s me in a cameo role behind the counter – no, I’m just kidding), getting the real Durant arrested. This allows Peyton to intercept a bunch of money from one of the real Durant’s gangster friends in Chinatown. Everything goes fine…until the real Durant shows up…and Peyton’s Durant-face starts to melt in the hot, California sun (they say just twenty minutes is too much these days…ever since we lost the ozone layer…there’s a one-percenter joke for ya).

This conceit obviously brings up questions of identity, both for our over-stressed anti-hero and for the film as a whole. Despite looking like a refugee from Rob Botin’s special effects workshop, Peyton really could chose to look like anyone. Over the course of the film, he winds up portraying every member of Durant’s gang, sometimes more than once. It’s a nice “diversion,” (or we’re meant to think he thinks of it as a diversion) but of course Peyton’s really just killing time until he can whip up one extra special face – his own – out of one special batch of skin…the kind that won’t melt in an hour and a half.

Later on, Peyton will insist to Julie that if he covered his burns and

“…lived behind a mask, you could love me for all I was inside. Without pity.”

Like the Universal monsters and Mad Scientists before him, Peyton knows exactly what he looks like, and his primary motivation is self-hatred. But because hatred is an all-consuming bitch from which there is no escape

“…as I worked in the mask I found the man inside was changing. He became wrong…A monster…I can live with it now, but I don’t think anyone else can.”

This is where Darkman really succeeds: by having the courage of its convictions. It’s a simple film that doesn’t forget to be ambitious; an authentic tragedy about a good man driven to horrible things by horrible circumstances beyond his control. Like Bruce Wayne’s parents, Peyton was in the wrong place at the wrong time. He just happened to survive and come out the other side with super powers. An official un-person, he holds up in his new lab and becomes an ever-more-mad Scientist, his mission to perfect the fake skin repeatedly sidelined in favor of murdering everyone who took his real skin from him.

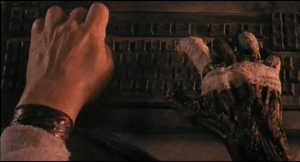

There’s a scene where Peyton accidently lets his bandaged hand get too close to a Bunson burner. It sparks up but, thanks to the surgery, he can’t feel the pain. He gets to watch his hand burn with the kind of shocked – but detached – surprise we’d all have if we were in his position. He smothers the fire and looks at the result. “They took my hands!” he says to his empty warehouse. He doesn’t mean this literally – the hands are right there, he can see them, and even if they are insensate they still take orders from his brain. Instead, he means “they” (Durant? the doctors? Julie?) took the individuality those hands symbolized, what with their one-of-a-kind markings indicative of Peyton Westlake and Peyton Westalke alone.

He struggles with this throughout, constantly talking to himself or his warehousemate, the cat, desperately attempting to hang on to his only innate superpower: a rational, scientific perspective. It allowed him to create the skin in the first place and, by God, it will allow him to perfect it if he only works hard and long enough. Or so he tells himself. That’d be hard enough even for a normal trauma victim and it eventually proves impossible for Dr. Westlake. I imagine he picked the deserted warehouse specifically so he could take the occasional Insanity Break, rush downstairs, and work out his uncontrollable rage by ripping lead pipes out of the walls.

Scenes with Peyton as the Phantom of the Waterfront pay homage to all the Universal horror films Raimi and I watched when we were young. Raimi’s manic little directorial asides attempt to add depth to those old tropes by locating us firmly and completely inside this monster’s head space. By creating a series of montages through superimpositions, whip-pans, quick intercutting, and reoccurring motifs of fire and cackling, the film instantly locates us in Peyton’s fractured, Ferris wheel of a mind, and spending time there will either leave you howling with laughter…or make your cry. It all depends on whether or not you ever cried at the end of Frankenstein. (C’mon, admit it! You did! Don’t look at me that way. The Shadow knows.)

These days, though, the way this script treats Julie is what really makes me cry. Not only does she drop the whole “Evil Capitalist bribing people” thing in the wake of Petyon’s “death,” she suddenly grows a case of The Idiocy. She mentioned this whole thing to Strack around eleven a.m. and, by six, her boyfriend’s place was a barbecue pit. How could she not put two and two together? (Hell-oh-oh! Jules? Anybody home?) How could she dance with the bastard? To say nothing of have the kind of relationship the script implies they have, post-Petyon? That’d be like Lois Lane shacking up with Lex Luthor after Superman’s funeral. How could Julie not bat an eye when Peyton suddenly reappears without a scratch on him? Almost as if he’d made a mask and gloves out of that synthetic skin you know he’s been working on for years…the skin you two were discussing first thing in your first scene together. Gah. Topping it all off, she up and tells Strack Peyton’s alive once she follows Peyton back to his lab and discovers his Dark Secret. But since she’s got no reason whatsoever to suspect Shrack (until she finds the MacGuffin Memo sitting right there on his desk in plain sight) all this does is give Strack news he can pass on to his silent-but-deadly partner in crime business, Robert G. Durant. And set up Julie’s Inevitable Kidnapping, of course.

I’m sorry, but this is Script Induced Stupidity of the highest order. On behalf of the human race, I’d like to apologize to Frances McDormand for the way her character got shafted. Damnit, why can no one write women well? I’m really starting to get sick of it.

Despite that, I’ll never get sick of Darkman. No one’s even tried to replicate this movie’s crazed mix of pulp crime, superhero action, and melodramatic tragedy. And they shouldn’t. I’m not even sure Raimi himself could pull it off now that he’s been through the Spider-Man wringer three times (each more painful than the last). Infinitely riffable, Darkman is nevertheless well-done in spite of itself. It overcomes its own flaws to become as unique as any of the other films associated with Raimi’s name.

The real tragedy is, making Darkman was such a hassle Raimi swore off the studio system for the next five years. He shook hands with the Devil and used Dino De Laurentiis’ cash to make Army of Darkness. After that hit big, he did his damnedest to break into television, eventually succeeding with a little something called Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and a little something else called Xena: Warrior Princess. And while those series got a lot of people (myself included) through adolescence, their success left Darkman to suffer in that least-comfortable of Purgatories: the land of direct-to-video sequels.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

One of the best superhero movies. Sam Raimi’s visually deft direction makes Darkman enjoyable. It looks and feels like a comic book.

Although I actually saw Darkman II & III first… both of which I remember being a lot better when I was a kid…

They were a lot better back then by virtue of being the only game in town. Since Darkman’s TV series never caught on and the books are harder to find than pigeons in Liberty City, I personally took whatever I could get…even if it did star Arnold Vosloo.

Specifically, it feels like a comic book from the early Dark Age, and I can’t recommend Peter David’s critique highly enough for its point-by-point breakdown of all the similarities. If I ever adapt this review into a video I feel like I’d almost have to use that as a framing devise to provide additional structure.

Horrible to think what the message was to a 5 year old – is this where the idea that altruism is for fools came from? Or “no good deeds ever go unpunished”? I watched it too but don’t remember how it ended. Not well for the protagonists. No redemption through love in this one? No wonder good men give up -revenge is such an empty suit. And it’s Easter Time and the fifth day of rain. Play some Dylan and relax.

Not that I believe there’s any conscious message in this film…besides “pulp superheros are awesome, kids! Create your own! It’s fun! And educational!” But actually, I drew a lot of solace from the fact the film, by invoking Gothic horror tropes, stripped the superhero story of its sentimental bullshit, leaving something that – while by no means “realistic” – has a degree of verisimilitude missing from bigger-budgeted, more traditionally optimistic, superhero stories. That’s why Darkman hasn’t really aged at all these past twenty years, while the Fantastic Four films already look as dated as 80s college comedies.

It’s not that “altruism is for fools.” There’s barely any altruism in Raimi’s universe, and what little there is comes to us from poor, maligned-by-the-script Julie Hastings. Callous cruelty is the order of the day and, as such, a major factor in Darkman’s origin. Well meaning surgeons, their hands tied by circumstance, do as much to create this murderous monster as Durant, Strack and their cronies. If this film has anything to say about altruism I think it’d be something along the lines of, “Altruism is for the brave, the principled, and the good. But fair warning: it will be seized upon, at every conceivable turn, by evil assholes raised on the Gospels of Wealth and Ayn Rand. They are callous, cruel, and they are everywhere. In our society they hold high office (sometimes, as in Strack’s case, literally) and command great power. They will not hesitate to destroy you and everything that you are if you stand in their way. They’re absolutists and vulgar Marxists engaged in a bitter class war…that they’re winning. And even under the best of circumstances, good people can do serious harm to themselves and others, usually for the noblest for reasons.”

And as depressing as that sounds, at least it’s the truth. Lies about the Redemptive Power of Love aren’t helping anyone.

Isn’t not being able to feel pain a real, crippling medical condition rather than a superpower (for exactly the reason mentioned in the review ie when you stick your hand in a bunsen burner nothing makes you take it away) ?

Indeed, yes. Various stages of leprosy can cause similar effects, particularly in congenitally cases. But the one you’re probably thinking of is congenital analgesia: a rare mutation (every estimate I’ve read rounds things off to maybe 100 cases in the entire frikken world which sounds grossly low, but what can you do?) of gene SCN9A. This results in malformation of the sodium ion channels in the dorsal root ganglion, the transmission hub between our central and peripheral nervous systems. Apart from an inability to sense extreme heat or cold, a sufferers’ sense of touch functions normally…until it comes time for their peripheral nerves to give their brain damage reports. The lines of communication are closed, or were never laid down in the first place, so patients have to watch out for all kinds of stuff we norms take for granted. Like biting off the tip of your tongue in the middle of a conversation. Or rubbing your eyes so hard you scratch the corneas. Or heat-stroke, since it takes a lot to make someone sweat if their brain doesn’t even know they’re heating up.

Here’s a typically-maudlin 20/20 clip from 2006 (I think), which uses the blanket term “hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy (HSAN)” to describe the condition (HSAN could describe any one of five disorders, but the name sure sounds good in voice-over). The documentary they sample is Melody Gilbert’s 2005 A Life Without Pain, which follows three children – one in Minnesota, one in Norway, and one in Germany – with the same condition, and the daily trials and tribulations they must endure.

Interesting discussion on Darkman as well as the sequels. I never realized how similar Darkman is to RoboCop…

http://alan-smithee-podcast.s3.amazonaws.com/asp48.mp3

An excellent podcast! Wonderful, in-depth examinations of the trilogy…and its ultimate failings.

Check out their other episodes.

http://alansmitheepodcast.wordpress.com/

I listen to these guys regularly. They discuss one good movie and one bad movie, like Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. They have also talked about the careers of filmmakers (John Carpenter, Tim Burton and Quentin Tarantino) and the rise of the summer blockbusters.

Their Revenge of the Nerds episode is a special treat for me, personally. And with the revelation that Darkman 2 should’ve been Darkman 3 (and vice versa) I think the last few mental tumblers just clicked into place. I know what I have to do now…vengeance will be mine!

Good review, I wrote a review of this movie in November 2010 and came to a lot of the same conclusions. I missed your point about Julie though; considering how many female friends I have, I feel rather stupid now. One thing, though. In one of your comment entries when you are commenting about the place of altruism vs. Raimi’s world view, it was a good synopisis, but you lost me at “Marxists.” How are the villains Marxists? They seem to lean more toward the extremes of capitalism to me.

Stare into the extremes of any political system and it starts to look a lot like its nominal opposite. I didn’t mean to imply they were “real” Marxists (or “Classical Marxist” in the Scholar’s Tongue), but “vulgar Marxists”: those who hold with theories that came out of the Second International (whether they know it or not), that economics determines every facet of human civilization. Hence the scholarly euphemism (which also functions as a handy slur) “economic determinist.” The economic determinist logic goes something like this: “Man [sic] is driven by nothing more or less sublime than self-preservation. Man [sic] obviously invented economics to aid that purpose. And, since economic realities under-gird all our social and political ones, economics determines everything.” For the prole on the street, this was meant as an educational, consciousness-raising bit of doctrine. But that didn’t stop the aristocrat in his castle from absorbing those pieces of Marx that reinforced his worldview.

Over the course of the 20th century, these ideas, stripped of their Marxist origins, became the “common sense” philosophy of rich twats from Maine to Manilla Bay. Lots of upper-class cats balked at the idea of Revolution, but plenty of them dance to the “economics determines everything” tune. Probably more today than at anytime in history. For what is extreme capitalism – the mass economic self-aggrandizement we see in reality as often as in fiction – if not rich people’s mad scramble for (what they see as their own) self-preservation? Hell, the sharks at the top of the foot chain (like Strack) are as insecure and paranoid as anyone. They’ve got so much to loose, plus they’ve got to leave some “legacy” behind when they die, so they see the world as a constant network of threats to their own survival.

This state of mind is very much akin to Classical Marxist alienation of labor, except rich people don’t “labor” in any classical sense. This doesn’t stop them from equating what they do (even if it amounts to “sitting on their ass, dreaming up new ways to skim 0.0003% off of an international financial transaction”) with “labor,” just like they equate “survival” with “amassing bigger piles of wealth than [insert their version of The Joneses here].” They spend most of their time indenturing our political and social realities to the service of their economic one…mostly through “payments” like those Julie uncovered. “Bribes,” to call a spade a spade. And, thanks to the educations they bought themselves with all that lovely money, they are the most self-conscious class in America (which is partly why, when I was a kid, they still tried to pretend the U.S. was a class-less society). They know exactly where they are in the grand scheme of history. They know we outnumber them and, even with all their power, that still scares them shitless. Hence their bitter and on-going war against the other 7 billion of us.

Wow, you learn something new every day.

I present these reviews under Fair Use for the purposes of education…and entertainment.