I knew this would happen, if for no other reason than that this is the eleventh motion picture in the Star Trek franchise/canon.

I knew this would happen, if for no other reason than that this is the eleventh motion picture in the Star Trek franchise/canon.

Good Trekies will know exactly what I mean by this broad, sweeping generalization. Ever since William Shatner ran Star Trek V into the ground odd-numbered entries in the series have always been looked upon with suspicion, if not outright derision. I suspect The Final Frontier is itself responsible for this prejudice, but no matter. Tonight’s entry reaffirms its basis in fact, along with all of my worst expectations.

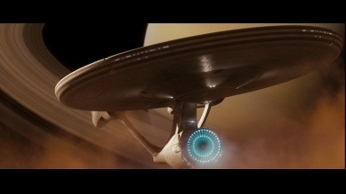

Star Trek begins on exactly the wrong foot by omitting even a pastiche of Jerry Goldsmith’s opening music (saving that, paradoxically, for the end credits). Director J.J. Abrams steps even further into it with a long, vertigo-inducing pan across the bow of the U.S.S. Kelvin. This being sometime in the twenty-second century, the Kelvin is a lone Federation starship, no doubt on some five-year mission to blah-dee-blah-dee-blah. Said mission is interrupted by the appearance of what “looks like a lightning storm” in space. Unfortunately for everyone aboard, the storm disgorges a gigantic ship which easily overwhelms the Kelvin, kidnapping its captain and forcing all hands to the escape pods.

All, that is, save the XO—Lt. Commander George Kirk. In a meant-to-be-heart-wrenching scene, Kirk overhears the birth to his son, James Tiberius, on an outward-bound life pod. He’s just enough time to tell his wife how much he loves her before his kamikaze run on the gigantic ship reduces him to superheated gas.

And, yes, here’s the infamous convertible scene, where in we see a pre-pubescent Kirk (Jimmy Bennett) trash his (stepfather’s?) convertible. Nokia must’ve paid through every hole in their head for that two seconds of product placement. Somehow, I doubt Gene Roddenberry had a place for evil, wire-tapping, international telecommunications corporations in his optimistic vision of the future. They’re certainly absent from mine.

Less well-known is the following scene, showing a pre-pubescent Spock (Jacob Kogan) reacting violently to the verbal abuse of his fully-Vulcan fellow-students. The proud Star Trek tradition of showcasing aliens who look, act, and speak exactly like humans, no matter their developmental stage, continues into the twenty-first century. Spock’s father, Sarak (Ben Cross), tells his half-breed child “Spock, you are fully capable of your own destiny. The only question is: which path will you chose.”

Any long-term fan will recognize this for the bullshit false choice that it is. Spock, the character, resolved this little identity crisis long ago (dying and coming back to life will put a lot of things in perspective—just ask Jesus, or Superman), finding the obvious answer in another question: why the hell can’t I be both? The fact that one can be both, and so much more within the benevolent fascism of the United Federation of Planets, is one of Star Trek‘s implicit messages.

But nevermind that. Fast forward a few years. Finding a totally-illogical, speciesist prejudice even in the high halls of the Vulcan Science Academy, a more-adult Spock (now played by Heroes’ Zachary Quinto) leaves to join Starfleet.

Back on Earth, Jim Kirk (now Teen Scream poster boy Chris Pine) hangs out, hits on a young Uhura (Zoe Saldana), and suffers a bar fight for his troubles. Only the intervention of Captain Christopher Pike (Bruce Greenwood) saves him from dying alone and unmourned in the suspiciously-California-looking fields of Iowa. Aboard the transport to Starfleet Academy, he meets a Kentucky doctor with more than a few phobias about space travel, name of Leonard McCoy (Karl Urban).

Back on Earth, Jim Kirk (now Teen Scream poster boy Chris Pine) hangs out, hits on a young Uhura (Zoe Saldana), and suffers a bar fight for his troubles. Only the intervention of Captain Christopher Pike (Bruce Greenwood) saves him from dying alone and unmourned in the suspiciously-California-looking fields of Iowa. Aboard the transport to Starfleet Academy, he meets a Kentucky doctor with more than a few phobias about space travel, name of Leonard McCoy (Karl Urban).

Three years later, we find Kirk cheating his way through the Kobaiashy Maru test, drawing the sublimated ire of one Commander Spock, who programmed it. Thankfully, the gargantuan ship that destroyed the Kelvin intervenes, staging an attack on Vulcan. With the rest of the fleet out taking a piss, it falls to the Academy’s trainees to man the fleet’s newest flagship, the U.S.S. Enterprise, in an ill-conceived attempt to counter this latest invasion of the Federation.

Plot contrivances and predictable “coincidences” work to bring the crew we all know and love together, compounded all the while by Kirk and Spock’s perpetual dick-waving contest. This is a Buddy movie, and submits to all of that sub-genre’s worst conventions: verbal sparing leading to physical one-upsmanship, leading to a one-scene reconciliation which (we’re meant to infer) makes up for all the horrible things each participant has said and done to the other, allowing them to become fast friends.

All of which would be annoying enough even if I couldn’t see the end of this story coming like fire from the clouds. It’s two writers, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman , keep the surprises to a minimum, secure in the knowledge that modern audiences will reward them for the most pedestrian of efforts. The few surprises they allow to slip through are just that: pedestrian, played for laughs that inspire only groans from this long-suffering critic. In one scene, McCoy injects Kirk with a vaccine that reduces him to a stumble-bum, the better to sneak Kirk aboard ship under medical regs. In another meant-to-be gut-buster, a young Montgomery Scott (Simon Pegg) winds up stranded inside a series of tubes thanks to that best of all possible Star Trek cliches: the transporter accident. Sulu (John Cho) utilizes his fencing (re: movie sword-fighting) skill. An enthusiastic Red Shirt dies and it’s all in good fun. Har, har, har.

Even I have to give the filmmakers props for a few key things, including the one “surprise” that actually works in this film’s favor: Leonard Nemoy’s appearance as Spock Of the Future. His inclusion in the proceedings is the one good idea in an otherwise uneven patchwork of a script. Seeing his face, hearing his voice—simply watching the man work in a role he not only made, but defined—after an hour of staring at all these Hot Young People, is a breath of fresh air. The best scene in the film comes near the end, when the two Spock’s meet at last, showcasing what this film might have been were it crafted by the hands of artists rather than bean counters, money-grubbers, and greedheads.

Acting here is spot on, not really the problem. Every cast member effectively channels their respective characters without slipping into parodies of the original cast. The illusion takes some time to congeal, particularly with Chris Pine, becoming seamless eventually through sheer exposure. Pine’s “I’m A Rebel With A Dead Dad” act is annoying, causing him to lag behind the rest of the cast, and his ability to convey emotion is Shatner-esque only in the sense that he’s terribly ham-handed. Thankfully, he’s the only weak link in a truly ensemble cast. Quinto’s Spock, Urban’s Bones, Cho’s Sulu, and Anton Yelchin’s Chekov deserve special mention for carrying the film between it’s too-frequent action sequences. Extra special, extraordinary mention goes to Zoe Saldana, for animating Uhura’s role as The Chick with more emotion than ever.

And I must say, Eric Bana (still the best Bruce Banner for my cash) creates his evil, future-Romulan character, Nero, out of absolutely nothing, turning a one-dimensional villain into a believable antagonist through the sheer force of ACTING! Thank you, Mr. Bana. Now get back into those purple shorts.

And I must say, Eric Bana (still the best Bruce Banner for my cash) creates his evil, future-Romulan character, Nero, out of absolutely nothing, turning a one-dimensional villain into a believable antagonist through the sheer force of ACTING! Thank you, Mr. Bana. Now get back into those purple shorts.

It should come as no surprise that the nauseating Mission: Impossible III was Abrams’ first and only directorial credit, until now. After piloting that train wreck, the Powers That Be should’ve banned him from even the cheapest digital camera. To say nothing of the fact that this is the man who co-wrote 1998’s Armageddon. For the past three years, he’s directed occasional episodes of Alias, Jimmy Kimmel’s talk show, and (of all things) The Office, seemingly devoting most of his time to wringing money out of the Machine. His efforts in that direction gave us Cloverfield and Lost, allowing him to satiate his addiction to Shakycam. Abrams has also fallen into the annoying habit of shinning lights right in his audience’s face. These “flairs,” as he calls them, add a level of unreality to an already out-there flick, paradoxical sabotaging the filmmaker’s attempts at realism. For God’s sake, man, leave the camera in one place and don’t try to give your audience seizures.

Beyond that, there’s the meta-problem, an inevitable consequence of allowing filmmakers raised on Star Wars and Indiana Jones (some of whom even admit that the Tim Allen spoof Galaxy Quest is their favorite “Trek” film) to make a Star Trek movie. I could go on and on about the philosophical difference between Trek and the dreck churned out by Spielberg’s and Lucas’ imitators, but, sufficient to say Star Trek is not a succession of shoot-outs and last-minute-save action sequences. Even First Contact, the most kinetic of the films, paused occasionally to talk about something more: the aspirational drive at the heart of humankind, the instinct that drove us over hills, across oceans, and into the stars. That, more than anything, is what’s really missing from this film, sacrificed in order to make room for Kirk (and Spock) to emote.

Complete lack of concern for Star Trek continuity combines with a low-opinion of the audience’s intelligence to insult each and every one of us, a special talent perfected under the Hollywood cell-phone and smog cloud. The fact that this film takes place in a wacky, parallel universe created by time traveling, Romulan shenanigans is the one bone Abrams and company threw to we long-term fans. Logic thus allows me to completely dismiss this film, the way I dismissed Captain Scott Bakula’s holodeck delusion of a TV series, which shall remain nameless.

Complete lack of concern for Star Trek continuity combines with a low-opinion of the audience’s intelligence to insult each and every one of us, a special talent perfected under the Hollywood cell-phone and smog cloud. The fact that this film takes place in a wacky, parallel universe created by time traveling, Romulan shenanigans is the one bone Abrams and company threw to we long-term fans. Logic thus allows me to completely dismiss this film, the way I dismissed Captain Scott Bakula’s holodeck delusion of a TV series, which shall remain nameless.

One step up from the Series We Dare Not Name, and a step down from 2002’s already-uninspired Nemesis, 2009’s Star Trek is a film I’d like to forget. Pretty but dumb, it will no doubt inspire a succession of increasingly-flawed sequels, forcing me to acknowledge it over and over again. How long do you think it’ll take before I look back upon this film with fond memories and declare it the stand-out entry in J.J. Abrams’-Star Trek series?

Probably not that long.

One does not make new Star Trek fans by reducing Star Trek to this uneven mush, shoehorning Star Trek‘s characters into formulaic action movies, or recasting them with younger actors. I don’t really care who you use, so long as you put them in a story only Star Trek could tell. Any monkey with a charge card can whip up a starship fight. Few have the narrative balls to place that starship fight inside of an uplifting meditation on the human condition. That is, was, and must forever be the pulsing heart of Trek. Otherwise Gene Roddenberry will come again in glory from the clouds to smite us for the vicious sinners that we are. He is still up there, you know? You’d all better watch your asses.

![]()

![]()

![]()

I’m of two minds with this film. I grew up with the original series (yes, I am that damn old) and that’s always been my favorite aspect. Even today, a solid majority of those old groaners still hold up, despite the space hippies and chicks stealing Spock’s brain.

For this film, I saw it in the theatre and liked it, but have no desire to see it ever again. I absolutely hated the “let’s just trash the continuity with time-travel!” aspect of it, as if 40-odd years of universe-building should just be tossed out because, Hell, because we can.

The acting I thought was fine, the one stand-out (for me) being Karl Urban. I really could see McCoy’s beginnings in that guy. The lens flares bugged the freakin’ heck out of me (as they did for the “How It Should Have Ended” guys) and I found most of the CGI as convincing as the “humor” – not much.

Oh, and in my opinion, it is Star Trek V that cemented the “odd-number” curse. The first film is slow and a bit stodgy (though surprisingly watchable and with a score tied for best in the series). Star Trek III is actually a pretty good film, it suffers mostly because it’s in between two outstanding films.

Thanks to the magic of syndication, I got to grow up with the original series as well. For me, Star Trek is 10 a.m. on an eternal Sunday morning tinted yellow by a rising, Midwestern sun. So the idea of a series reboot did nothing annoyed the hell out of me on general principals, for exactly the reason you cited.

And I’m glad to see I’m not the only Star Trek III partisan in existence. I’ll never understand the enmity Search for Spock inspires. Even as a kid, trapping Spock’s “living spirit” in Dr. McCoy’s body struck me as one hell of an Idea…a film in itself…the Genesis planet and Christopher Lloyd’s Commander Kurge shot the film up to a high place in my youthful pantheon, where it still sits. I had to live through Generations and Insurrection before the odd-numbered curse really sunk in for me. Then this film comes out, hammering the point home.

Star Trek III is not between two outstanding films.Wrath of Kahn is watchable but hardly the masterpiece everyone claims. Star Trek IV:Save the Whales is an embarrassment.

On this we, sadly, disagree. But I’ll address these points in my upcoming series, “Remedial Trekology.” (Perhaps.)

“Search for Spock”‘s bad rep is almost entirely reflexive. When cornered, I can’t really find anyone who has a truly legit reason for its low ranking (“The Klingons have Fu Manchu mustaches!” doesn’t really count). Yeah, as my dad said, it’s what Hitchcock called “Pictures of people talking,” but in this case, they’re saying interesting things.

At the time, you know what would have made an interesting follow up to ST3? Star Trek: The Motion Picture. No, wait, hear me out. We have a totally new Enterprise, a Kirk too popular too fire, so shunted into administrative work, an odd, unformed Spock anxious to be completed as a Vulcan, McCoy retired…it woulda worked, I tells ya. You know how I know? Because the surrounding plot elements of Star Trek IV are the same! An alien probe disables everything on its way to Earth, attempting to communicate with someone long gone…it even gets into the details, like Spock’s education, Chekov’s injury and the fact that the only weapon used during the whole film is against an inanimate object (asteroid, door knob).

Well, cough. Enough of that. Star Trek IV as it was, was a very nice film though the score is the worst in the series, so bad it makes it hard to watch.

Oh, and I should mention one personal ST3 triumph on the old B-Movie Message Board. When it was announced that William Shatner would host a beauty pageant at some Genesis Center in Ohio, I replied “Genesis?! Genesis allowed is not! Permits many…money–more” and got a round of applause from Mr. Shumate himself.

Oh, and just to add: I first saw Star Trek III on video, not really knowing anything about the film, and the SPOILER ALERT!!! destruction of the Enterprise totally kicked me in the gut. I stood up, jaw agape, as it happened.

Great review (and I was fine with the movie.)

J.J. Abrams should have directed the Star Wars prequels.

Now, now…there’s no need to go around giving anyone any bright ideas. Bad enough Lucas is already converting both trilogies into flash-in-the-pan 3D. Re-release season starts up again next year.

You were saying?

Having seen some of the trailers for the new thing, my main reaction is “how far can you push a Trek film in the direction of generic sci-fi actioner before it is no longer even slightly Trek?”.

“Nero, out of absolutely nothing, turning a one-dimensional villain into a believable antagonist”

I have to disgaree. Nero was one-dimensional villian and a superior actor would not done much better in such a miniscule role.

I am, nor have I ever been, a Star Trek fan but I know a bad film when I see one. When I see films like this, I am just digusted by the excess and no effort in real character. When Goldfinger came out, what is often considered the granddaddy of summer block busters, that relied on a popular image AND strong actors. Star Trek had (some) strong actors but they were ultimately muffled by the noise and relying on a long established franchise.

Yeah, you’re right. Frankly, I was grasping at straws, both as a Trekkie and as a reviewer trying desperately to mention something, anything positive at all. Nothing doing, of course, so I held on the the flimsiest of threads, since they were the only ones available. The plague of lens flairs stunned my brain as effectively as any phaser.

The action was just over kill in the movie to say the least. Even when Kirk and Spock where kids, they had to kick ass and take numbers in some over the top fashion. You got no sense of character from anyone in the film. It was basically a TV movie with a huge budget. You are also right about the lens flare. Yeesh.

Its obvious Abrams and Co. looked to turn Star Trek into a cookie-cutter action movie from the start, the better to lure in audiences jonesing for their Transformers fix, unable to wait until June. I expect they’ll continue that formula well into the next decade, provided aliens don’t invade L.A. at some point in the interim.

David. You, me, and my friend. We burn Hollywood. I have enough gasoline and rags. I’ll leave you my number…

Hey David. Love the site. Glad to see I wasn’t the only one to see that the Emperor had no clothes.

The sad thing is that there WAS a decent STARFLEET ACADEMY script written that stayed true to the series. Kurtzman, Orci and Abrams merely ripped it off and dumbed it down. You can read about it here:

http://www.aintitcool.com/node/22789

Dumbed it down while upping the fan-service quotient in a desperate attempt to assuage fan fears…which turned out to be entirely justified. Get ready for #2, which probably won’t have any clothes either. Our days of snickering at the Star Wars fan’s internal disputes are well and truly past.

As big a Trek fan as I readily admit I am (I have two Trek-related fonts in my Fonts folder–where do I submit my coolness card for revocation again?), I’ve never been one to research the whole history of each film in the franchise. I’d rather just evaluate the film on the merits of what’s up there on the screen. That said, I’d love to know just where some of the ideas in this film came from. The two incidences of product placement in the film floored me (I saw the Nokia phone in the car and at once thought of the “For the N-Gage!” running joke on “X-Play”). I guess that’s one of the uglier aspects 21st-century filmmaking that we’re stuck with. The film should have spent more time at the Academy than it did; Uhura’s Orion roommate offered a spark of a really good idea, seeing how students from differing cultures learned to work together. Ben Cross as Sarek and Winona Ryder as Amanda…um, not really. Cross is too emotional, Ryder not enough. And what was up with Scotty’s furry friend?

The answer to all your questions is, “the ideas for this film came from absolutely the wrong people.” Who were, of course, rewarded for their horrible ideas with showers of money, accolades and money. But we’ll get there next year. Pray for something other than a Wrath of Kahn remake.

Sort of a “post commentary” for this review. I have been beefing up my Star Trek knowledge and I have watched most of the original films and TV shows. I can safely say that The Undiscovered County is my favorite Star Trek film followed by the very humorous and surprisingly very effective Voyage Home. Out of the TNG movies, I have only seen Nemesis but you know what ? The film is not nearly as bad as everyone makes it out to be. Shinzon is actually one of the most compelling villains in the series’ history. He could have been the best but he was divided between the anger and frustration of having a meaningless existence and being the big bad guy in an action film. I’d say cut out the B-4 shit, add the political intrigue of Star Trek VI, and you would have probably had the greatest Star Trek film ever. Hell, I’d take Nemesis over JJ Abhrams’ action schlock any day.

To me, Nemesis, J.J. Trek and the first two and a half seasons of Enterprise all share certain fundamental problems that have nothing to do with Shinzon. And we are as one on “the B-4 shit,” as you so accurately put it. And The Undiscovered Country. But see First Contact, at least. You owe it to yourself, Starfleet, and America.

What I meant to say is, Shinzon saves Nemesis from being without any sort of merit. Both Picard and Shinzon share some very engaging scenes. And yes, I will check out First Contact in the future.

Okay so I finally saw First Contact. It was decent action picture overall. Not as offensive as the Abrams films though I was still rather unfulfilled but thankfully, unlike Generations and Nemesis, the Data subplot was not only good but it was the best thing about the whole movie. The only thing that irked me really was Captain Picard; he was totally out of character. TV show Picard would been shocked by the reckless, revenge crazed psycho named Jean-Luc in this movie. Overall, I still have give Nemesis the edge because of Tom Hardy’s performance and his more pathetic side of Shinzon.

i decided to re-watch this last night, even though it took SIX YEARS to get the stain off my soul from the last time. decided i’d go in with a post-modern, deconstructionist approach, and judge it without reference to ANY prior incarnation of Trek. and whaddayaknow? IT STILL SUCKS. even on its own terms this flick is total failure–no matter what exposition it engages in, 10 minutes later it is COMPLETELY contradicting itself. it does have some pretty pictures, however. unlike y’all, i’m to old & cynical to see Leonard Nimoy’s appearance for anything other than the pathetic attempt at fan service that it is. post-modernism aside, it’s a universe TOTALLY DEVOID of Gene Roddenberry’s vision of the future. Not only are 23rd century Humans still a bunch of fucking assholes, EVERY OTHER race in the Universe is, TOO!! the Vulcans are SO delusionally hypocritical as an entire race that they genuinely deserve to die. feh. all that being true, the scene of Kirk’s birth STILL chokes me up, and i didn’t get till now that Kirk’s dad is THOR!!

and you were totally right when you opined that it would probably only get worse…..

also, throwing my 2 cents in, until this abomination, the Worst Trek Movie is Nemesis, because it’s just a 2-hour, poorly disguised ad for a video game. just re-watch the action sequences and you’ll see what i mean.