I’m sorry. That title line should read,

“And now, fought with the terrible weapons of Super Science(!), menacing all mankind and every creature on Earth comes: THE WAR OF THE WORLDS!”

So our Humble Narrator concludes as the black-and-white pre-title montage of World War stock footage gives way to the bright, technicolor titles of this, the Alien Invasion movie that inspired all subsequent Alien Invasion movies. All of them – from the Independence Days of my childhood to the Battle: Los Angeles of today – owe their existence to this…which in turn owes its own existence to Orson Welles.

Picture Welles, writer/actor-about-town in the mid-to-late 30s, making a name for himself in radio thanks to his golden voice and flair for the dramatic. Those two talents combined into a perfect storm on October 30, 1938, when Welles adapted an old sci-fi novel you might or might not have heard of into an hour-long radio drama so damn good, it caused mass panic (or what newspapers reported as mass panic the next day). The extent of that panic is debatable. What it did for Welles career isn’t. Neither is the fact that, overnight, H.G. Wells War of the Worlds became the hottest property in Hollywood.

They tried to make Orson Welles direct the damn thing himself, but he refused on principle, going off to make some stupid bio-pic of William Randolph Hearst instead. War of the Worlds languished in Development Hell for next two decades, going through more script drafts and personnel changes than a 20th Century Fox superhero movie. Then something happened and that something was “the ’50s,” which saw many a penniless sci-fi writer move west to try and seek their fortunes in Hollywood…including future genre god Robert A. Heinlein.

In 1950, already-famed producer George Pal bought one of Heinlein’s scripts and turned it into Destination Moon, the first authentically “hard” sci-fi film to achieve popular success. It did so by removing most of the genre tropes that kept sci-fi confined to the B-movie and pre-movie serial ghetto. No rocket packs, no jump-suited, alien civilizations…just good, ol’ fashioned ‘Merikans and their race to beat the Others (who went unnamed in Destination Moon, but were obviously the Soviets). Destination Moon made so much bank, Pal became the natural choice to (finally) produce War of the Worlds. In doing so, he accidentally created the modern, Hollywood blockbuster.

Oh, sure, that term’s an inaccurate descriptor of this film. But watch War of the Worlds again and you’ll see almost every modern trope of the Alien Invasion and Total Fucking Disaster genres. The tough-but-socially-awkward hero; his fawning, screaming, preening, one-dimensional Love Interest. The way both are swept up in a world-wide cataclysm, finding themselves used by a film that cynically manipulates its audience into thinking it’s whole hell of a lot deeper than it actually is. I don’t know what that sounds like to you, but, to me, that describes about 60% of modern genre movies, including wides swaths of many well-known director’s careers. Bitch about bad CGI and camera set-ups that ape real life disasters all you like. This slavish adherence to story structure is what really twists my knickers.

So let’s see…after the credits, we get a brief prologue from our second Humble Narrator of the film: fine British actor Cedric “Dr. Livingston” Hardwicke, who uses the opening lines of H.G. Wells original novel to take us on a tour of the solar system, starting with Mars. Here, our planetary neighbors are represented by massive, detail paintings by the Father of Space Art, Chelsey Bonestell, whose work you should find at once. Then hang it on the nearest available wall. Stare at it. Contemplate how nothing you’ll ever draw could possibly be as awesome as Bonestell’s crappiest cover for F&SF. Repeat as needed.

This is how you opened a movie in a world without PBS – with luxurious, languishing pans across paintings of the planets, while dry facts are read to you by a drier British actor It’s like Hardwicke’s telling a particularly fucked-up bed time story to his Amazing Stories-addicted children, and his sonorous tones could very well lull someone to sleep…if he were talking about anything other than the Martian’s planned invasion of Earth.

Strange meteors rain down across the globe, seeming to keep their noses up, cutting wide swaths of destruction through the countryside. Since giant hunks of space rock should leave massive impact craters wherever they arrive (as they did in Wells’ novel), Pacific Tech physicist and Manhattan Project veteran Dr. Clayton Forrester (Gene Barry) – his fishing trip interrupted by a nearby strike – theorizes that these things must, in fact, be hollow.

But, with the meteor still cooling down after re-entry, there’s little for Dr. Forrester to do but run into town with the hot college student (and fan of his work) he meets at the impact site, Sylvia Van Buren (Anne Robinson). And just in time for the local square dance ho-down! Yee-haw!

Then comes my favorite non-mass destruction related scene in the film, as director Byron Haskin inter-cuts Dr. Forrester’s square dance with the final moments of three rural SoCal stereotypes: The Slack Jawed Yokel, the Enterprising Huckster and Token Hispanic Man. I love these three more than the entire main cast combined, because unlike the other broad stereotypes running around this whitewashed version of California, these three actually evidence flaws. The naivete of their rural America hopefulness (as expressed by urban Americans looking back on their idealized childhoods) kills these Three Amigos, as sure as any Martian heat ray. Why else would they march up to it, waving white flags?

The heat ray knocks out the town’s power and casts an electromagnetic field over everything, stopping watches and scrambling radios. Dr. Forrester, TV’s Slyvia and Sylvia’s uncle, the town pastor (Lewis Martin), all rush to the crater, with the military close behind. Tension mounts as the fields around the meteor blacken, and a great alien War Machine rises from the crash site. Pastor Collins tries one last-ditch effort at inter-planetary understanding. It goes over about as well as Dr. Arthur Carrington’s attempt, two years earlier, in Alaska (that is, not at all).

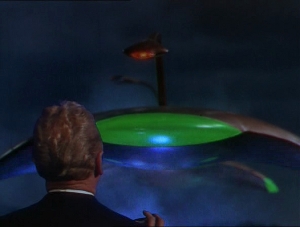

If Michael Bay had directed this, we would’ve had twenty jump-cuts between the square dance and the Three Amigos, or Pastor Collins and his now-distraught niece, and we would’ve missed what I always loved best about these aliens: the way they move. Stiff and metallic, it (purposefully?) clashes with their design sense, with its preference for threes and smooth lines that meet at curved angles. The result, when set to a hollow, clicking sound track that reminds me of mechanical crickets (really multiple electric guitars, played backwards), is unnerving in all the right ways. Suitably alien, its another testament to great sound design’s ability to enliven.

Along with good directing. There’s real grandeur in the way Haskin shoots these war machines. The way they’re revealed – slowly, but ominously – is perfectly handled, playing up a dread until we see them in full…and, after that, things don’t get any less dreadful. In their machines, these Martians are a credible and creepy threat, cementing an apocalyptic tone for this picture that overrides most of the silliness its accrued since its original release.

Because he’s an Heroic Scientist in an early-50s, sci-fi film, Dr. Forrester has the ability to fly a plane. Wouldn’t you know it, he and Sylvia immediately come across one as they flee the Battle of Hill Valley (or whatever the town’s called). It’s neither the first nor the last deus ex machina to fall into Clayton’s hands (the first being Sylvia herself), but it’s the one that strands Our Heroes in a farmhouse behind the lines.

For a moment, the film follows General Mann (Les Tremayne), last survivor of the first crater, as he organizes the retreat and communicates the seriousness of things to Washington. Through him we learn that, across the globe, Martian war machines are blasting through the best humanity has to offer. This is enough to convince General Mann (who, with his mustache and his brisk manner, reminds me of a 1950s Terry O’Quinn) and his superiors to drop the bomb.

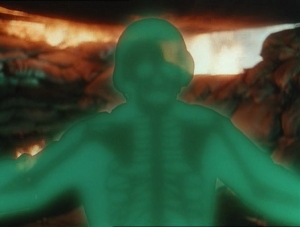

Unaware of this (for now) Our Heroes hold up in a farm house…but because God moves in such mysterious ways, he drops a Martian meteor right on top of them. Now comes the sequence that influence so many modern directors, with Spielberg neither first nor last among them, as the Martians search the wreckage for any human stragglers. Our Heroes cock up their chance at staying hidden by trying to explaining things to the audience.

On foot…these Martians are not so impressive…their electric eye of a periscope looks like the ass end of a vacuum cleaner with a real long hose, strung up by off-stage wires. The Hayes Code prevented these Martians from being the real existential horror shows they were in Wells’ novel – giant heads without bodies, snatching people up with metal tentacles and draining them of blood to feed their colonies of budding young. Too bad Howard Hawks gave that thrust for blood (and a plant-like reproductive cycle) to his Thing two years earlier. But this was an age where you weren’t even allowed to discuss human reproduction in the movies, so the absence of Wells’ treatises on Martian biology is understandable.

As is the Martians’ continued influence on movie aliens and their large scale invasions. They want our world, they’ll burn us down to get it, that’s all we really need to know, and the film tells us that in its (second, post-credit) prologue. The rest we learn as the characters learn it, which is how we should’ve learned all that stuff about Mars at the start. Fleeing their farmhouse (right before a War Machine makes it flame on, of course…ancestor of all those “Good Guy runs away from an explosion” shots we see these days), Dr. Forrester and TV’s Sylvia (no, really – she reprised this role for the War of the Worlds TV series in 1988, after Friday the 13th and Star Trek: The Next Generation suddenly made TV shows based on movies cool again…for about two seconds) are swept to the front lines. There, they observe that even man’s greatest weapon is useless against Martian Super Science. Or, as General Mann puts it in the trailer shot:

“Guns, tanks, bombs: they’re like toys against them!”

Many have noticed and commented upon the marked similarities between Godzilla and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (which saw wide release two months ahead of this). Me, I’ve always wondered about what influence (if any) War of the Worlds had on Gojira’s original conception. Both are inexplicable threats from traditional sources of Chaos (the sea and sky, respectively). Both utilize devastating atomic heat rays as their primary weapon. And both are neigh-invulnerable to conventional (or, hell, even un-conventional) weapons.

It’s something I like to think about, because I’m sure as shit not thinking about Our Heroes. Barry and Robinson are fine actors, but their outclassed by the War Machines. Plus, once the Martians start making mass murder happen, Clayton and Sylvia’s survival becomes downright unbelievable. At least Wells’ Narrator traveled alone, and for good reason: the Martians killed damn near everyone he spoke to over the course of the story. It was a bleak examination of “modern” industrial warfare (warfare “fought with the terrible weapons of Super Science,” you might say) and its effects on a First World country.

The best critical interpretations of Wells’ novel I’ve read see his Martians as sci-fi stand-ins for the Germany of his day – the recently-united, industrial powerhouse, with its own dreadnoughts and pretensions to beat England in the real life game of Risk they called “world politics” in Wells time. Newspapers contemplated the bombardment of London on a near-daily basis, and Wells’ novel concludes with his protagonist viewing a heavily idealized vision of “the Mother of Cities”: deserted, damaged…but not destroyed, and in its complete desertion, ultimately beautiful. For one thing, without all that factory smoke in the way, you can climb a hill and actually see the damn city.

There’s no such Gothic Romanticism here. It may have been filmed in Technicolor, but it’s not a Hammer movie. I’ll let special guest commentator Sylvia Plath (or her avatar, the anti-Mary Sue, Esther Greenwood) tell you what the early years of Technicolor were like:

I hate Technicolor. Everybody in a Technicolor movie seems to be obliged to wear a lurid costume in each new scene and to stand around like a clotheshorse with a lot of very green trees or very yellow wheat or very blue ocean rolling away for miles and miles in every direction.

It was the CGI of its age, every present and annoying in its Brechtian distancing. It’s at least as important to the way modern movies look as the advent of sound and I can’t imagine this film having nearly the impact it had were it in black and white. It would be just the kind of B-list, sci-fi picture its makers hoped to avoid. Hence the large budget, an outrageous amount of it poured into special effects. So that’s another trend, set.

Things pick back up once Dr. Forrester gets his samples of Martian tech and Martian blood back to his lab and supplies the trailer with its other iconic line,

“We now know we can’t beat their machines – we’ve got to beat them.”

The trio of war machines attacking Los Angeles have other ideas, forcing Clayton to load everything up and get the heck out of dodge. Here’s where the film starts piling problems on our protagonist in order to drive home its point (or “MESSAGE!” as we say these days). I can accept the military letting its pet Scientist get his shit together, even after the evacuation order comes down. But I can’t imagine them letting him do it without a full, armed escort, if only to prevent exactly what occurs when Clayton drives into a mob of Los Angelenos, just as desperate to escape as he. They mob his truck, pull him from it, and toss his equipment into the street to make room for more escapees. Anarchy’s descended. Civilization, like anything else on the receiving end of a Martian heat ray, is withering. Like the zombie fox said to the Green Goblin, chaos reigns.

As he comes to realize this, Clayton staggers through the wasteland that was once a bustling metropolis, crying for Sylvia, his sanity more or less giving way. Gene Barry’s given the chance to display some actual range range for the first time since the Martians came out of their hole, going from manic desperation to relief when he finds Sylvia in (where else?) church. If only this movie had the courage to kill off Our Happy Couple as they stood comforting each other. I would’ve given it full marks.

Instead, the biggest and most blatant deus ex machina in the genre saves Our Heroes (and, indeed, the entire human race) at the eleventh hour. Yes, where man and Martian, in their shared hubris, tried to conquer Chaos with machines, God “in his great wisdom” conquers all with “the littlest of creatures”: terrestrial bacteria.

Step back far enough and this becomes a Greek tragedy – and interplanetary Iliad I don’t think anyone intended to make. If we take Our Humble Narrator (who’s straight-up reading from Wells’ novel by this point) at his word, this is the story of God pitting his children against each other in a fruitless, wasteful fight with a foregone, predetermined conclusion. Bittersweet, really, since we never learn if the Martians value death in battle the way the ancient Greeks did. It, along with so much else, was a question for further generations of science fiction to take up.

But none of them would exist without this. So, despite its cardboard characters, frequent resort to convenience and weak ending, I still love the damn thing for getting there first with the most. It is the standard by which I judge all Alien Invasion pictures because it is quite obviously the standard by which they judge themselves. Its first forty-five minutes are awesome and, despite not living up to them, the second half is still better than all but a hand full of other, similar movies I could name…but won’t.

(Yet.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When I was a kid I was really disappointed that the Martians didn’t have their tripods. As an adult it makes more sense. The movie’s setting was 1950’s America not Victorian England. In order for them to seem like a real threat they had to be technologically superior to us Earthlings. Tripods are cool but force fields and levitating engines of doom are something to worry about.

Apparently Pal and Haskin originally conceived of following Wells designs to the letter…but neither could wrap their heads around just how tri-podal locomotion might work, or how such a thing might be made to look as cool as it needed to look on screen. Haskin and Dr. Forrester compensate for this with a few insert shots of crackling, electromagnetic fields that make up our war machines “invisible legs.” You have to freeze-frame to make them out, but they’re still there in spirit, and I’ve always felt their invisibility increased the Martians ambient creepiness.

I loved this movie as a kid, but as I’ve gotten older I noticed what you highlight here: this is the ancestor of modern Sci-Fi summer spectacles, with weak characters and a lot of convenient story elements. Like you say, the pluses outweigh the minuses and there are some great scenes, particularly in the initial confrontations. I got to see this at a theater, once, with only two other people (my oft mentioned brother and a friend) in the audience and we had a ball with it, it really is great in that context. I love Plath’s quote about early Technicolor films, because it is so very true and often very distracting; unlike you, I wonder if a Black and White version of this film might not be MORE tense, though I suppose they wouldn’t have poured the same resources into it and certainly the Martians would look less awesome.

I think the soundtrack is what makes this movie. Specifically, the sound of the Martian Head Ray being fired. Unforgettable !

Yes! That little chorus of de-tuned string instruments has stuck in more minds and inspired more nightmares than any other, save the chirping of Them‘s giant ants or the thrilling, contra-bass growl that originally gave Gojira voice…though that last one’s probably just my personal bias.

Oh, hell yes. I first heard it while watching a clip show of sci-fi movies involving aliens that I think was put out to promote the release of E.T. and the sound really helped the images stick in my head for years.

I love Technicolor personally. What I think didn’t help was the use of such heavy lighting. Hollywood did not break out of that nasty habit until about the mid 1970’s.

In general, I am huge fan of War of The Worlds. I think it’s gripping to see the humans on the defensive; They were fighting what seemed to be a hopeless war. The ending is weak but it’s not entirely unjustified.

And hell, that is the best looking alien spacecraft in a film ever made. Those precious days before George Lucas’s boxes and cheese wedges became the standard for sci-fi films.

I first saw this film when I was about three or four…and it gave me nightmares (I still have them from time to time…can’t wait for the next one).

The spin-off series, the Tom Cruise remake, all the other remakes (yes, someone did a War of the Worlds and War of the Worlds 2 (The Next Wave))…none of them compare to the George Pal version…it is awesome.

I’ve read the first book of the H.G.Wells book. I don’t want to read the rest because I know what happens. I’d rather leave it where mankind’s last hope, the ironclad Thunderchild, lies at the bottom of the sea.

The 1953 War of the Worlds film has to be the film I have watched the most, even though it always ends the same. At least in the nightmares I don’t know what’s going to happen (though one time the end credits came up when I overslept).

I read the book at age ten during a “classical SF” period my father got me into. He was a Wells fan of the Old School and we had quite the spirited discussion of War of the Worlds merits vs. my personal favorite of Wells’, The Invisible Man.

If you really want to get a kick out of something, find Volume 2 of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comics, which details the League’s involvement in the Martian Invasion of 1898. It is also awesome, in the fullest possible sense of the word. And it’ll help you forget that fucking LXG movie (and all the awful War of the Worlds remakes) ever existed.

I was in love with sci Fi films at a very young age. The ‘ 53 film will always be the best War of the World’s for me. JB

I know what you mean. I feel exactly the same way.

There is only one War of the World’s and I’ve seen it 53 times.

My sentiments exactly.