The 1980s saw a remasculization of American cinema. After long years languishing inside various genre ghettos (from sci-fi to vigilante to blaxploitation), the Action film took on a shambling semblance of life all its own. When you look at Westerns, Cop Dramas, or Spy Pics from the 60s and 70s, distinct hallmarks of their diverse genres remain apparent, intact. By 1982, with First Blood, we see these conventions reincarnated as a horrific Frankenstein of a thing, neither fish nor foul. A death mongering genre that dominated the Industry well into the 1990s, putting butts in seats worldwide with its fetish for explosions and ever-more-elaborate weaponry.

The 1980s saw a remasculization of American cinema. After long years languishing inside various genre ghettos (from sci-fi to vigilante to blaxploitation), the Action film took on a shambling semblance of life all its own. When you look at Westerns, Cop Dramas, or Spy Pics from the 60s and 70s, distinct hallmarks of their diverse genres remain apparent, intact. By 1982, with First Blood, we see these conventions reincarnated as a horrific Frankenstein of a thing, neither fish nor foul. A death mongering genre that dominated the Industry well into the 1990s, putting butts in seats worldwide with its fetish for explosions and ever-more-elaborate weaponry.

The late-80s saw the genre reach its (*ahem*) creative height. Beginning with 1985’s Rambo II, and continuing through Lethal Weapon, tonight’s subject (both 1987), and director John McTiernan’s next film, Die Hard (1988), the Action movie grew comfortable with its internal logic (or lack thereof) and began to stretch its wings out, taking on new and strange shapes its finely-trained audience hardly recognized. McTiernan himself would drag it through several of these bends, leading the genre to high highs with…well…let’s say Die Hard: With a Vengeance…and eventual suicide. (Well, what else can you call Last Action Hero?) {More}

After an obviously tacked-on bit of pre-credit narration, explaining the movie’s plot, D-War launches us onto the most audaciously stupid journey I’ve seen in a long time, beginning with the most audaciously stupid directorial decision of (most likely) all time: a triple flashback…explaining the movie’s plot. Again.

After an obviously tacked-on bit of pre-credit narration, explaining the movie’s plot, D-War launches us onto the most audaciously stupid journey I’ve seen in a long time, beginning with the most audaciously stupid directorial decision of (most likely) all time: a triple flashback…explaining the movie’s plot. Again. As if anyone doesn’t already know, Watchmen is an award-winning, twelve-issue comic book created by the writer/magician Alan Moore and the artist Dave Gibbons, originally published by DC Comics in that dark and distant year of your lord, 1986. Steeped in Reagan-era pessimism and dreams of nuclear holocaust, the book did more for superhero storytelling than all Frank Miller’s work combined. It dragged the genre, kicking and screaming, into the late twentieth century, disguising its social relevance with a baroque self-reflexiveness now recognized as the hallmark of comic’s Iron Age.

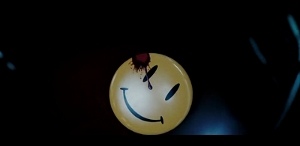

As if anyone doesn’t already know, Watchmen is an award-winning, twelve-issue comic book created by the writer/magician Alan Moore and the artist Dave Gibbons, originally published by DC Comics in that dark and distant year of your lord, 1986. Steeped in Reagan-era pessimism and dreams of nuclear holocaust, the book did more for superhero storytelling than all Frank Miller’s work combined. It dragged the genre, kicking and screaming, into the late twentieth century, disguising its social relevance with a baroque self-reflexiveness now recognized as the hallmark of comic’s Iron Age.