In 1951, science fiction movies took two booster shots to the arm and entered into the public consciousness on a scale so grand that, looking back on it now, it’s like watching a dam burst in slow motion. So much so that one can easily drown in the torrent of “creature features” America produced in the 1950s. All thanks to two films that defined the boundaries of their sub-genre, enlivening hoary old tropes by dragging them, kicking and screaming, into the twentieth century.

One of those films, which we’ll consider in its own time, was The Day the Earth Stood Still. The other, released five months before, was The Thing from Another World. You can try and find a stranger pair of siblings…but I don’t really want you too. These two are all I need because they were all the genre needed at the time.

Prior to their release, science fiction was a joke, laughed at and bemoaned in turn by polite society, allowing it to become the sole province of nerds. The Thing irrevocably welded Sci-fi to Horror and saved both genres from their separate decline into self-parody and stupidity…as evidenced by another “great” film from 1951, Abbot and Costello Meet the Invisible Man. The world was six years away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the old monsters had lost their grip on the collective amygdilla. New monsters – in a comfortably Frankenstein-ish mode, to be sure, but still – were already moving back in the shadows, ready to pop through the first conveniently open door and take your head off with a casual swipe.

It’s 2011 now. The Thing from Another World‘s had its 60th birthday back in April and, like so many movies, it’s been remade twice already by studios hoping to overwrite the originals in the public imagination. That’s helped me decide to review this Thing, because I know there are some sad sacks out there who’ve never seen the original and labor under the delusion that horror movies began with John Carpenter.

I know because I was once one of you. And I was lucky: I had my father. He would’ve been four when this movie first came out and, even if he missed its first run, I’m positive he caught a revival showing sometime around age seven. Either way, this movie scared the Bejesus out of him and he passed this tale onto me one day as we stood staring at the Horror section of our local video store…which didn’t have a copy of this Thing, of course. It’d been remade in the early ’80s by a studio hoping to overwrite it in the public imagination. I had to wait until the magic of satellite TV brought a thousand and one hours of horror – classic, modern and everything in between – to my little house in the shrinking woods before I saw this Thing in full.

Imagine twelve-year-old me bundled up on the floor in the middle of night with my father’s relayed memories playing in my head. Not the best way to watch a movie, to be sure: interrupted every fifteen minutes by agonizingly long commercial breaks. But The Thing from Another World is all about triumphing over adversity so, no surprise, I wound up enjoying the film more than Carpenter’s remake.

This is a Howard Hawks production, so I can’t really tell you how much of it was actually “directed by Christian Nyby.” Hawks was a veteran of what we now call Classical Hollywood, when producers ruled the roost from dung heap to weather vane. As a credited producer, no one really thinks he just stepped aside and let Nyby have a free hand, though the two had worked together closely on Red River, which Hawks actually directed, with Nyby serving as that movie’s editor. Hawks’ partisans will point to the naturalistic dialogue and strong female lead (for the early 50s, at least) as evidence of ol’ Scarface’s hand at work. Maybe they’re right. Maybe making Red River together was just so damn much fun Hawks and Nyby temporarily fused into some manner of super being. I don’t know, or really care in this context because, together – along with a whole bunch of other people – they created the most iconic alien invasion film of 1951…that isn’t named The Day the Earth Stood Still.

The set up’s familiar now because so many have spent the last 60 years ripping this movie off: an isolated-but-representative group of stalwart Heroes square off against an Unearthly Menace. The north pole provides the isolation, a group of Army flyboys and civilian scientists make up the stalwarts, and James Arness – two years out from the role in Gunsmoke that would make him famous – provides the Menace. While it’s true this movie is a transparent anti-communist and anti-scientist screed it’s survived thanks to the universality of this set-up…see also, all those rip-offs, the most famous being Ridley Scott’s Alien. The fear of lonesome isolation and its attendant vulnerability isn’t going to go away anytime soon.

Know what has gone away? Nice long introductory character scenes, where we meet and greet the Meat before circumstances force them into action. Captain Pat Hendry (Kenneth Tobey, who’d go on to play Col. Jack in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms), USAF, will stalwartly represent All-American Goodness for the evening, along with his co-pilots, Lts. Mac (Robert Nichols) and Dykes (James Young) (insert your own joke here). Their boy Scotty (Douglas Spencer, two years away from where I’d first meet him in Shane), will be Our Reporter for the remainder of the film, cracking wise and perpetually stymied by his inability to turn all this into a scoop. A less-secure director might’ve made Scotty the viewpoint character. When a call from General Fogerty interrupts Cap’n Pat and the boy’s card game, Scotty says it, “Sounds like the old days,” with a completely insane amount of nostalgia for the War these people obviously fought and won together.

Then again, everyone in the room’s had six years to repress all the horrific trauma they experienced, paralleling everyone who would’ve sat through this film’s first theatrical run. Just to underline that parallelism, everyone in the room’s a bit on edge, owing to the fact they’re sitting across a frozen ocean from Those Damn, Dirty Ruskies. At least investigating last night’s mysterious “meteor” impact out on the ice, which seems to’ve FUBARed both communications and compasses, gives Cap’n Pat’s crew something to do with themselves while they wait for World War III. After all, as Cap’n Pat notes, the downed object “could be Russian. They’re all over the pole, like flies.”

Our Heroes stop off at the civilian research station nearest to the impact site, Polar Expedition Six. There they meet the rest of the cast and get some useful directions from Six’s scientific celebrity in residence, Dr. Arthur Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite). In a scene that’ll have ADD sufferers among you fidgeting, the “good” doctor leads Cap’n Pat through a slide show of “meteor” impact pictures, patiently explaining all the wonderful ways that “meteor” refused to behave like a meteor (all of which boil down to “it changed directions, seemingly under its own power”). Unfortunately, patiently and painstaking explaining yourself to the audience, based on the false assumption that your film will attract 100% of the coveted mouth-breather demographic, hasn’t gone anywhere in the last sixty years either. Afterward, though, and with a bit of help from (what else?) their Geiger counters, Our Heroes reach the impact site. There they discover that, to quote Scotty,

“We’ve finally got one! We’ve found a flying saucer!”

This was only four years after the flying saucer boom began with a mid-air encounter above Mount Raineer, Washington and a now-much more famous crash-and-recovery op near Roswell, New Mexico. By 1951, UFO investigations were well underway at both the Air Force and the FBI, though both denied it…due to professional embarrassment, I imagine. After all, “men from Mars” were the exclusive province of sci-fi writers…which is why every sci-fi writer who read a newspaper during this era got to sit back, feel smug and say, “See? We told you so! Back in the ’30s, we damn well told you so. Just like we told you about the atomic bomb.”

The existence of The Bomb – a theoretical dream and one-time SF plot device brought to horrifying reality through the power of Science(!) – hangs over most mid-twentieth century SF stories like a vulture’s shadow. That’s why no one really seems all that surprised to find the saucer…or too broken up when their efforts to free the saucer from the ice (with more bombs…because they solve everything) inadvertently destroys it. There’s a ho-hum, “Aww well, better luck next time, guys,” air to the destruction…and an even more subdued reaction to the discovery of a frozen “thing” a scant few feet away.

Back at Polar Expedition Six, Cap’n Pat sticks “that Thing” in the storeroom, posts a guard and orders everyone away, steamrolling over Dr. Carrington’s wish to have a good scientific go at “the Thing.” Creeped out by its frozen-open eyes, Corporal Barnes (William Self) makes the mistake of covering the ice block with an electric blanket…that’s plugging in and, somehow, manages to melt the ice without shorting out the whole camp (that’ll come a bit later). The Thing wakes, escapes the storage room…and gradually reveals its own malevolent biology as it stalks through Polar Expedition Six, picking off whomever it can catch. It needs blood, you see. Like H.G. Wells’ Martians (who’d come in force two years later), this Thing is an old-school vampire dressed in a modern onesie. It even uses the same reproductive cycle. Feed this Thing enough blood and it’ll just start budding. There were two and a half billion people on Earth in 1951. From this Thing’s perspective, that’s two and a half billion bags of free fertilizer.

This is the part where a genuinely-pretentious critic’s supposed to tell you, “this movie lacks modern sophistication and effects.” We know that really means “this movie lacks modern sophistication of effects” because this is no shape-shifting monster: it’s James Arness in a torn up flight suit with the kind of giant-brained headpiece Invaders from Mars and the pilot episode for Star Trek would go on to make synonymous with this era of SF. This Thing is monoform and the movie’s proud of it: much is made of the Thing’s plant-based origins, leading to one of Scotty’s best lines:

“Please, Doctor, I’ve got to ask this. It sounds like, well, just as though you’re describing some form of…super carrot.”

After a battle with Polar Expedition Six’s sled dogs (temporarily) deprives the Thing of its right arm Our Scientists cart the arm back, allowing everyone to poke at it and Dr. Carrington to wax rhapsodic about how being a plant means “it’s development was not handicapped by emotional or sexual factors,” making it “our superior in every way .” This is, of course, insane on a whole tiered system of a levels, and it’s the weakest part of the movie, the most obvious piece of forced conflict. Unemotional, asexual Science aligns itself with the Unknown Enemy, if only by not fighting it hard enough like the rest of these love and marriage- (i.e., sex-) crazed avatars of Common Sense.

The script treats Carrington the way medieval Inquisitors treated their prisoners, pressing him to death under a heavy weight of poor decisions and subliminal coding. He exists to be proved wrong because Cap’n Hendry must be right. After all, he’s the Designated Hero. Even gets The Girl in the end…spoiler alert…We’re told Carrington’s a Manhattan Project veteran, meaning he’s one of the Heroic Scientists that won the War for us…or he would be in a movie that didn’t view Science as (a) a monolithic Thing in its own right that (b) can never regain our trust again. Ever. Not after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As the Thing thaws downstairs, Pat tells his erstwhile Love Interest (and Dr. Carrington’s assistant) Miss “Nikki” Nicholson, that Polar Expedition Six’s scientific community “are kids, most of ’em; nine year old kids drooling over a new fire engine.”

Yeah, those damn egg-heads, what the fuck do they really know? Children, all of ’em. Nothing to do but infantilize, dismiss and marginalize them. They can’t be trusted, none of ’em. Look what “they” have already done to the world. Don’t turn your back on them for a second or they might just sabotage your plan to kill the murderous alien menace prowling around outside.

This anti-intellectualism, which twelve-year-old me found intolerable, is somewhat muddled by the key factor ignorance plays in moving this plot along. After Our Heroes accidentally destroy the Thing’s ship, Dr. Carrington says, “I should’ve thought…” Scotty shoots back a, “You sure should have,” ironically foreshadowing the end the movie. If Dr. Carrington were a human being instead of a Straw Man for Science he might’ve applied basic (or “scientific,” if you will) reasoning skills to his own situation. He might’ve realized piloting an interstellar craft is no guarantor of intelligence. After all, the United States of America has an Air Force filled with idiots who can still manage to fly planes…and land them. This alien crashed his ride into one of the most hostile environments on Earth…and then left the fucking ship…to no apparent purpose save crawling just far enough away to freeze solid. “Our superior in every way.” Yeah, Dr. Carrington. Sure. Rii-iight.

The worst thing you can say about this Thing is it’s a dumbed-down bastardization of John Campbell’s 1938 novella Who Goes There?, “based on” Campbell’s story the same way modern remakes are all “based on” the original screenplays. Surprise: Hollywood bought the rights to a story, ripped out the core concept, and tossed the rest in a dumpster next to all the dead hookers Marlon Brando was already leaving in his (already considerable) wake by 1951 (fresh off a little bit of fluff called Streetcar Named Desire). There’s a reason Dr. Carrington’s such a pompous, insane asshole…apart from propping up the layperson’s notions about not trusting smart people – or people who “don’t think like you or me” in general. (And we all know what that means, don’t we?) Carrington’s assholery adds some human conflict to this drama, allowing Hawks (or Nyby, whichever) to make the best decision they could make and keep their Thing offscreen for most of the picture.

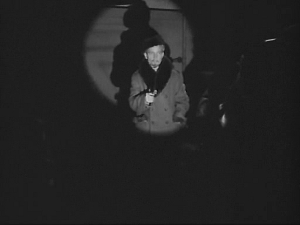

My father insisted he never saw The Thing in full light and he was right…to an extant. You never see more than flashes until the Final Showdown, after the perpetual cat-n-mouse game its played with Our Heroes forces everyone into one cold hallway outside the generator room. Those flashes are enough when you’re seven and you can be damn sure this Thing’s a hulking monster with gardening tines for hands. As an adult, your childhood perceptions are overwritten by the cold reality of whatever’s on screen, and the debt Arness make-up job owes to the Frankenstein monster becomes a little too clear for comfort. Best if they had kept their Thing covered up (insert your own rimshot here).

Still, there’s one brief-but-famous jump scare near the half way point that’s executed so damn well it still works sixty years later, even if you know it’s coming. Hell, I’ve seen that jump scare pop up in so many documentaries that, at this point, the scene works because I know it’s coming. The characters are all going on their increasingly hushed, not-so-merry way, splitting up into Army- (and film critic-) approved groups of two or three as they hunt the Thing through the halls. As many people (the most recent, from my point of view, being George Romero in a documentary I watched earlier this year) have noted, the people in this movie are always opening doors or shouting for someone to close them against the cold. As their situation clears, Our Heroes take to grouping in common areas, visibly flinching whenever a door opens. We the audience pick up on this increasing paranoia and, if you don’t find yourself flinching along with them at some point, check your pulse, because you’re obviously dead. As George said,

“We know that, sooner or later, The Thing’s gonna be there and…goddamn!”

Indeed, George. Indeed.

Time to talk about the thing that really holds The Thing together: it’s exponentially ass-kicking cast. As the human heavy of all this, Robert Cornthwaite gives a performance that’s more than exceptional – it’s iconic. Every jumped-up scientist who’s ever wanted to “communicate with,” study, or otherwise placate a monster owes something to Dr. Carrington, and with good fucking reason.

On the other side of the coin, and by the standards of Stalwart All American Heroes, Kenneth Tobey gives a surprisingly nuanced performance, loosing all of his Heinleinian Superman, SF character’s surety once the Thing begins draining sled dogs and scientists of blood. When Dr. Carrington tries to question Cap’n Pat’s courage, Our Hero summons up enough to openly admit he fears the Thing. This would be anathema to the previous generation of SF heroes (Rogers, Strange, Gordon – that crew) who never felt fear as a rule. Here, fear saves the human race because it’s the most ingrained fear in the history of the human race: fear of the Other…that which doesn’t “think like us”…whether it be within or without. Instead of emasculating him in our eyes, this bald admission of fear humanizes Cap’n Pat, props up the Thing’s air of menace and moves “our captain” closer to the object of his (and our) affection: Margaret Sheridan.

Yeah, Nikki…even if her pants start where he ribs end (and what pants they are…raowr), she’s the best foil Tobey could’ve asked for. Hawks chose well when he chose these two, rightly seeing they’d carry the film through the strength of their interplay. The real hell of it is, screenwriters Charles Lederer and Ben Hecht (with uncredited help from Hawks) bend over backwards to give Pat and Nikki an adult relationship, in defiance of the then-prevalent Hays Code and it’s Bigass Book of censorship rules. You have no idea how refreshing it is to see two characters in a 1951 film talk (even if only in the most oblique terms) about meeting each other during an Anchorage-based drinking binge. Or the drunken one-night stand that resulted from the above. “When I got up in the morning,” Pat says, “you were gone.” I can almost hear the repressed nebbishes of the time gasp in shock at hearing this. Assuming they had breath left after little exchanges like this:

Pat: What about that business of starting over?

Nikki: Well, I think I’ll buy you a drink this time. I think you’ve earned it. That is, if you want one.

Pat: You can tie my hands if you want.

Nikki: That might not be such a bad idea.

Pat: I mean that.

Nikki: Well, you suggested it.

Pat: Alright, I’ll bring a rope.

And he does.

The banter in this script sells its characters, leaving the actors to sell their roles, aided by Hawks’ way with dialogue. This is as good a collection of everyday, gun-toting military men as you’re likely to find in a monster movie because everyone treats their co-stars like old friends. People talk over each other, trade bad jokes, give Cap’n Pat shit about his burgeoning romance, make snarky commentary about other people’s Serious Pronouncements, talk shit about their General behind the General’s back, and generally try to process an extraordinary situation as best they can by pretending to act “normal.” They achieve a state of “hyper-normality” instantly recognizable to anyone who’s ever been trapped in a desperate situation with a group of people who don’t know what the fuck’s going on.

Dr. Chapman: Find anything, Captain?

Pat: Not a sign. We poked into every snowbank within miles.

Bob: Barnes flushed a polar bear.

Barnes: Sure did.

Dr. Chapman: Scare you?

Barnes: Not after I saw it was only a bear.

Only the occasional line of clunky exposition (“Dr. Carrington, you’re a man who won the Nobel Prize. You’ve received every kind of international kudos a scientist can attain. If you were for sale I could get a million bucks for you from any foreign government.”) spoils the illusion…and what else are Reporters like Scotty or Scientists like Carrington for? Whereas modern horror movie protagonists are whinny, screaming, profane assholes to a man, woman and child, these people are at least recognizable as people…even if they can’t curse to save their lives.

This is the key to this Thing‘s success. We spend the whole movie with these jokers and, because they look, act and sound like human beings (for the most part), we spend half a film pleased at getting to know them and the other half waiting for the Thing to walk through a door and whittle them down. This is everything – no, this is the only thing – a good monster movie should do. A good cast is the best special effect you can possibly have. Everything else is just window dressing.

The only things holding this Thing back are its mishandling of Science and shoehorning of a Designated Villain into a story that doesn’t really need one (cuz…ya know…rampaging alien and all). Plus, since it is the 50s, there’s plenty of cheese to be had for those of us who paid attention in Science class. My favorite? The ship’s radiation signature disappears as soon as it’s destroyed…because that’s how radiation works, right? The Thing itself is radioactive (the better for Our Heroes to track it with their Geiger counters) but no one bothers to worry about the danger this might represent to everyone’s health. Something tells me Pat and Nikki are gonna have some real trouble adding on to their future family…

My one real problem with this Thing is it eventually ends. And that’s the kind of problem I love to have with a film. If you haven’t seen it, do. If you have, watch it again. It’s another one of those rare classics that rewards repeat viewing, if only because there’ll be a line you didn’t catch the last time that will reach right out and grab you.

“That’s what I like about the Army: smart, all the way to the top.”

Like that. Because that is what you call “classic.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I need to revisit this one myself, but I’m curious-will you be reviewing Carpenter’s film? You say you prefer the original-fair enough-but do you like or dislike Carpenter’s version?

Oh, I like Carpenter’s Thing just fine…and that’s one of those sentences that’s just going to come out wrong no matter how I try to phrase it. I’ll get to it eventually.

I really wish the monster just killed that idiotic doctor.

Anyway, I love Thing From Another World which became the template for the combination of sci-fi and horror. Also as dumb as the doctor was, he gave the film a lot of credibility.

Indeed. What else is the power of SCIENCE for?

I love both this version and Carpenter’s. This version is more fun due to the character interactions. And Margaret Sheridan — yumm.

It’s hard for me to consider Carpenter’s version a remake since it adapts the actual story instead of just taking the bare bones.

Yeah, that used to be the Great Debate amongst Thing scholars…until this year. Now everyone’s playing “assimilate the prequel while ignoring its continuity gaffs,” but I’ll be damned if I join that hit parade. (The possibility for Star Wars flashbacks is far too great.) Funny how Carpenter avoided the “remake in name only” slur by not taking his source-movie’s full title.

One moment I enjoyed is at the end, when Scotty is broadcasting to the world. He says “Dr Carrington, head of the scientific expedition -” and there’s a beat, while he wonder if he’s going to tell everybody what a doofus Carrington is – “is recovering from injuries sustained in the battle.” Everybody smiles and pats him on the back, because the doc turned out to be an asset in the end, after all. One time, after it was shown on local tv, someone wrote to the Tv Answer Man “I watched it because it said ‘Starring James Arness’ but I didn’t see him. In fact, the only one in the movie tall enough to be him was The Thing” Answer: Yes, James Arness played the part of the Carrot From Outer Space. ” 🙂

Super Carrot From Outer Space, no less! Faster than a speeding saucer-man; more powerful than a delusional scientist; able to break glass windows with a single nose-dive! “Keep looking! Up in the sky!”

And you can still take the film somewhat seriously even when you can reduce the monster to just a vicious carrot. Thing From Another World is a fine illustration about how a little camp can go a long way.

Bundled up? On the floor? Shrinking woods? Isolated. This should have scared you, too. What a nerd you must have been – must be. Thanks for the insightful review of an old favorite. I’m gonna have to watch it again.

Everyone needs to, especially given how the remake’s dominated recent conversation.

Has anyone noticed the glaring flaw that runs throughout the movie? That even though these guys are in the Arctic, night follows day just like they were in a temperate clime, John Carpenter’s remake does the same thing.

Of course I still love the hell out of this movie, which scared the hell out of me when I was 11.