During the Dark Ages of VHS we relied on our memories and the word of mouth they helped shape. Tales of key scenes from key movies whose titles we could barely recall, chosen exclusively for their shock value, became a kind of fan short hand. If you struck up a conversation with some random convention-goer, you wouldn’t get, “Hey, did you see Lucio Fulci’s City of the Living Dead?” No. You’d get, “Hey, did you see that one where the priest hangs himself?”

Yes. Yes I have. It’s Lucio Fulci’s follow-up to Zombi 2, also known as The Gates of Hell or Paura nella città dei morti viventi (Fear in the City of the Dead). And despite being filmed on location…in America…and retitled with an eye toward the desperate Romero fan’s money, City has arguably even less to do with the Dead Mythos than George Romero’s last three Dead films. And I couldn’t be happier.

Because, you see, it’s a Lovecraftian film more than anything else (though old H.P. goes uncredited) and surprisingly effective for what it is…and what it is isn’t very nice. Straight adaptions of Lovecraft’s stories often run themselves aground searching for the right tone: a combination of existential dread and visceral revulsion that seems to occur to Fulci and screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti naturally. But like many a Lovecraft story, City bites off more than it can chew and ends on a somewhat unfulfilling note that just might ruin the whole damn thing for you.

It certainly strikes the right tone by opening with a priest (Fabrizio Jovine) hanging himself from a graveyard tree, inexplicably causing the cemetery’s moldering occupants to sit up and take notice. New York City seance attendee Mary Woodhouse (Catriona MacColl) also notices all this via the medium of astral projection. True to her Lovecraftian origins, Mary promptly drops dead from fright as soon as her vision concludes.

This puts the seance-holder, the Great Theresa (Adelaide Aste), afoul of New York’s finest and their chief exposition-prompter, Sgt. Clay (Martin Sorrentino). Far as Theresa’s concerned, all this spooky shit’s been foretold by “the Book of Enoch,” a four thousand year-old text that accounts for…something, certainly. We never really find out what and it has no real baring on the plot. Our Heroes certainly won’t do anything sensible with it…like take it with them, say…it foretold that a Gate to Hell would open so – and I’m taking a long shot here, but – maybe there might be some information about sealing the damned thing thing up again. Maybe. It’s worth thumbing through the index. After all

Theresa: At this very precise moment, it some distant town, horrendously awful things are happening. Things that would shatter your imagination.

With mind bullets! When you absolutely, positively, have to violate every known law of physics in the process of reaching your target, using only the best technology the United Federation of Planets has to offer.

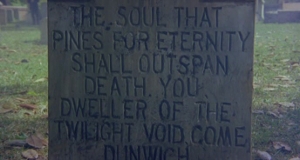

The titular City is actually the small “New England” town of Dunwich, now haunted by Father Thomas’ suicide and quite a lot of other weirdness besides. A howling wind laden with cloying billows of dust has migrated northeast all the way from the tiny south seas (or Carribian) island of Matool. Even the townsfolk call this Fell Breeze “very unusual.” We’re introduced to a strange cross-section of Dunwich’s populous right off, with quick, short scenes that exist to set-up scares more so than characters.

That, I think, is why this flick’s so often identified by its big-ticket, special effects shots. For me, the most effective one has nothing to do with zombies, ghostly priests, or Lovecraftian allusions. It’s the scene where Mary Woodhouse wakes up inside her own (partially buried) coffin. With one camera, some blue mood lighting, five fingers of stage blood, and a whole lot of screaming and clawing, Catriona MacColl gives us a vision of fear as universal as it is effective.

Made worse by Fulci and editor Vincenzo Tomassi, who cut Mary’s efforts together with shots of this film’s Reporter, Peter Bell (Christopher George). Hot on the trail of that girl what died during a seance and all, Peter just happens to be in the cemetery when Mary comes to. Paul begins to walk away. Close up on Mary, screaming. Paul turns with a “What the fuck?” look on his face but…an airplane just flew overhead. We see Paul ask himself Did I hear that? Really? This is only three minutes of the overall film but it’s so damn good it warps time itself. We’re there, on top of that cemetery hill. We are these two people: the one buried alive and the one up top, wrestling with that Really?

You can see here’s where City of the Living Dead grabbed me. After this I knew, even if the rest of the film sucked, I’d tell people to watch it just on the strength of this scene. It’s that powerful, that effective. It’s fear in a a hand full of shots. The driving force behind Horror as a whole (or what should be the driving force, at the very least).

I’ll admit, the film does start to peter out immediately after Peter…see what I did there?…grabs a pickax and rescues Mary from her grave. Protip for all you Heroic Reporters out there: don’t sink your pickax into the top of a coffin, use it to pry open the lid. For God’s sake, somebody’s head’s under there, and you’d look really stupid if you accidentally killed the person you were trying to save.

Also, that’s two reporters named Peter in as many zombie films, Fulci. Just saying: some of us notice these things.

As Mary and Peter unite in their search for Dunwich (which, according to Our Reporter, “isn’t even on the map”) City of the Living Dead becomes a bit sociological. The narrative bounces from story to story as Dunwich’s populous gradually falls to the Undead Hordes, seemingly led by the resurrected Father Thomas and backed by a growling, discordant, howl that sounds like the noise my stomach makes whenever I eat greasy pizza

Watching all these Everyday People snipe at, turn on, and eventually abandon each other to the Creeping Terror reminds me of Cronenberg’s early work in a good way. This also allows Fulci and Sacchetti to stage every Horror Movie sequence they could possibly dredge up from childhood. This is their cover album, their Garage Inc., made in the prime of their careers in homage to all the stylistic influences that drove them to do what they do and do it so well.

Like Pennywise the Dancing Clown, City of the Living Dead plays all the hits down here, from the Monster in the Closet to the Spring-Loaded Rat. From Being Buried Alive to the Doomed Couple Making Out In a Pickup. The female half of that Doomed Couple (Daniela Doria) is the girl who – in the film’s other famous scene – pukes her own guts out as she cries tears of blood. All thanks to the spectral (?) Father Thomas’ Penitence Stare. As the narrative pays off its set-ups, we notice the padre’s gained quite a number of postmortem superpowers. (Including off-screen teleportation.)

Mad props to Miss Doria for swallowing all that tripe…and then spitting it back up on cue. No props to the DVD transfer, though, which makes the fake head they used for close-up shots even more apparent. As of matter of fact, all the fake heads stand out now…but I suppose that’s the price we pay if we want our entrails to be their reddest.

Unfortunately, entrails steal the show from their original owners. As with Zombi 2, most of these Dunwich “characters” really aren’t. This forces me to take City of the Living Dead‘s title literally. After all, if (as Dawn of the Dead established) we are them and they are us, then the living of Dunwich become the narrative’s real zombies. Couched in the security of Small Town Americana (as seen through the eyes of Italians – why do you think all the priests are Catholic?) otherworldly horror sideswipes them because there’s so dang much worldly horror to go around. The funeral home proprietor steals jewelry off people’s dead relatives as they await burrial. The town pervert leads certain people’s Innocent Daughters off into the woods. Those Innocent Daughters aren’t so Innocent after all, their father’s are just idiots. Or murderers in their own right.

We see this in a character I like to call Pervert Bob (Giovanni Lombardo Radice). We first meet him as he’s about to get it on with his favorite inflatable sex doll. Thankfully Father Thomas’ howling backup band and the moldering dead baby that appears out of nowhere kills the mood rather quickly. For the first hour, City keeps checking back in with Pervert Bob as he encounters one worm encrusted corpse after another, fleeing from them across his down’s now-significantly-foggier landscape. As the disappearances mount, the town barflies and Sheriff place the blame on Bob. The town rumor mill quickly turns suspicion into certainty. Because of this, Dunwich looses those first few crucial hours at the beginning of every zombie apocalypse, before sheer math dooms us all to become some corpse’s brain food.

Culminating in Pervert Bob’s death by drill in a garage Father Thomas’ hordes chased him into the previous night. This is the other Shocking Act of “Violence” everyone uses to identify this film and I chuckle at the fact it’s a scene between two humans. It only shocks because Fulci doesn’t cut away when you’d think any sane person would. Bob, like his town, gets no opportunity to redeem himself.

You know what? All those convention goers were right. This is Lucio Fulci drilling a hole through Small Town America and forcing us all to watch. And I love it.

I love me some stories about small towns rotting away from the inside <shameless plug> so much so that I wrote my own, called Stygian, coming to a ebook retailer near you </shameless plug>. But I realize such stories often amount to a lot of scenes where people we don’t know (and thus don’t care about) die horrible deaths for apparently no reason. Such is City‘s unfortunate case. Once Pervert Bob dies, we loose the closest thing we had to a POV character and the rest of the movie suffers for it.

At least narrative threads begin to align once Peter and Mary (I know: where the hell’s Paul?) make it to Dunwich. There they hook up with the town shrink, Gerry (Carlo De Mejo) and his star patient, Sandra (Janet Agren) who by this point have their own Zombie Adventure stories to share. The movie throws its last real curveball when Our Heroes call to arms scene’s interrupted by a snowstorm of maggots the howling wind blows into Gerry’s office. In true Suspiria fashion, they’re squeaky maggots, and I can’t help but wonder if this is Fulci’s way of saying, “Yeah, fuck you, Dario!”

In any other film, I’d consider it a “fuck you” to the audience as well, but unlike most of the zombie films that rode Romero’s coat tails, City‘s very open about its supernatural reality warping. A dead priest opened up a gateway to Hell by committing suicide in a graveyard, it says. Of course maggot tornadoes are going to blow in through the windows. I joke about off-screen teleporting during the Gut Puking Scene, but all the undead display this power throughout. By the end, as Our Heroes near the Hellgate, zombies even resort to on screen telportation, the better to squeeze Our Heroes brain’s out through the back of their (suddenly fake) heads. Top that, Slasher Movie Killers. I dare you.

I’m torn as to whether or not Father Thomas’ new flock even count as zombies. They seem more like projections from some awful, otherworldly force. (Yog-Sothoth, maybe, I don’t know.) How else could they make your eyes bleed (or throw your bowels into open rebellion) just by looking at you? How else could they disappear if you’re not looking at them?

We have to speculate about all this because the story (such as it is) avoids any answers. The purposeful vagueness about Just What the Hell is Going On both enhances the atmosphere and annoys the crap outta me. It’s a cheap trick to justify all these Horrible Happenings. I even think Fulci and Sacchetti recognized this. Why else would they use a Portal To Hell (complete with its own Ticking Clock…set for All Saint’s Day, of course) as their big plot device? The couldn’t have been more obvious…unless they’d used the Necronomicon. The Great Theresa’s (not so great if you’re only in three scenes, lady) ranting about the Book of Enoch might lead Evil Dead fans to believe that’s exactly where this movie’s going.

But then again, no. City of the Living Dead is a different beast entirely. It’s actors labor under a thin script and barely-defined characters. All the men are square jawed (and fully bearded) and driven to action in the face of horror while all the women simper and weep blood. Either poor acting or the Italian habit of shooting movies without sound and dubbing all the dialogue in later one (makes international distribution that much faster, don’tcha know) gives everyone in the film a permanent case of Dull Surprise.

This is unforgivable, especially in the face of an imminent apocalypse, because if they’re not going to react to Father Ebola and his worm-feeding minions (past taking the occasional swig of Jack Daniels) why should I? The ending doesn’t help, because how could something like this end satisfactorily? On top of that, the photography lab apparently ate Fulci’s original ending long after he ran out of cash.

If you can get past all that, this movie is the perfect example of dread, inexorable as an Old One and thick as the Dunwich fog. Weak characters and shallow plots are a dime a dozen in modern horror, but because the people making this film made it with an obvious passion for their material, City of the Living Dead stands out today, probably even more so than during its first run. Fulci’s aesthetic tricks (like zooming into everyone’s eyes, as if playing chicken with everyone who saw Zombi 2; or lighting all the Dead from below, the way we light ourselves when we tell campfire ghost stories) are certainly put to better use here than in Zombi 2, and they give the film as much of an identity as its sheer volume of collected tropes.

It’s not perfect, it’s non-standard, and it’s not stingy with the squishy stuff, but City of the Living Dead is a stylish Evil Little Town movie that attempted to be all horror movies to all people. Maybe it over-reached, but that wins more points with me than an army of ex-MTV directors ticking off genre check-boxes. We all know they’re the real zombies, am I right?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Great review. One thing of note in this Fulci zombie movie (and Zombi 2) is that all “important” characters have Biblical names: Peter, Mary, David, etc. Poor Daniela Doria… having to spit up guts, only to return on year later to have her in-movie boyfriend carved up in the prologue to “The House By the Cemetery”. Oh well, such is the fate of b-movie starlets, I suppose. Are you per chance reviewing the Catriona MacColl triptych, David?

Well, you’ll just have to stick around and find out now, won’t ya?

David, has it occurred to you that once past the death scene of Emily (played by ravishing Antonella Interlenghi, is it me or does she look a lot like Dollhouse actress/general hottie Miracle Laurie, minus the bountiful bosom?) the music does a lot of cues to the thematically similar The Beyond/L’aldilà (which was released the year after) and even Zombi 2 (which was released the year before)? I watched again yesterday and it just struck me. A question: Pervert Bob thwarts the priest’s assault two (three?) times by sheer…. “luck” – only to get killed by one of the parents. Why did the priest spare him, do you think? Going from his sparse backstory (as town bug eater/weirdo) he had the qualifications of sexual vices that the other victim had. You have any views/theories on that?

I got the impression that Pervert Bob was this movie’s version of those two peasants from Hidden Fortress…or the droids from Star Wars. We see most of the narrative through his eyes – the eyes of Dunwich’s lowest social order. I don’t think Father William spares him for any great reason beyond the audience need for a point of view character. Most of the other town’s folk are walk-on parts, aside from the Obligatory Child, and we the audience need recognizable faces to lead us through all this. Until Our Reporter and Psychic Girl make it to town, of course.

Now that you mention it, that’s true. Also, Gerry the Shrink (Carlo De Mejo) and Pervert Bob are introduced roughly around the same time, after Mary’s fatal séance. It’s actually quite inventive to see Dunwich and its inhabitants through the eyes of two very different social groups: the yuppie upper class (Gerry) and the lower middle class (Bob). I wouldn’t call it “social critique” as such, but for an Italian cheap splatter flick that’s quite a cerebral achievement.