And then there was Campbell Scott, son of the great George C. and co-director of the award-winning 1996 drama Big Night. That film became the darling of mid-90s critics everywhere, earning itself a regular place on the newly-created Sundance Channel. From there, it entered my eyes and proceeded to make absolutely no impression on me whatsoever.

So you can imagine my surprise when I saw him turn up in a Jazz Age version of Hamlet on…the Hallmark Channel…I know, right? It was the year 2000, I was seventeen at the time, and seventeen-year-olds channel surf. So sue me, I wound up watching Hamlet on the Hallmark Channel. Having seen three movie-Hamlets in the previous decade (four if you count that episode of MST3k), Campbell Scott’s production convinced me the man had gone insane. The ghost of Hamlet’s dead father possessed his script for a Great Gatsby movie. So I’m skipping over his third movie, Final, to talk about Off the Map. Because Sam Elliot’s in this one. And he’s always awesome.

Just watch: Final will turn out to be the one Campbell Scott movie I actually enjoy. That’s just how these things go. Off the Map isn’t bad, it just has all the problems of a slice-of-life drama in this age of hand-held cameras and Gus Van Sant. Problems of focus, problems of scope, and problems of basic story structure. Problems born of filmmakers who sacrifice telling stories on the alter of formalism. In the end, they make weird little movies where not much happens and nothing really pays off in the least. Movies that insist you either take them as they are or they’ll take you down a rabbit hole of supplementary reading. That’s the only way these films will ever answer any of the question you might have while waiting for the characters to do something interesting. After all, isn’t it the question that drives us? In my case, the eternal question is always, “Well, what the fuck was the point of all that?”

Off the Map is the story of the Groden family, three independent souls living the good life in the New Mexico wilds. It’s also the story of “the summer of my father’s depression.” This we hear from their only daughter and the closest thing we have to a main character…at least through the film’s first half…Bo (Valentina de Angelis). Bo’s adult voice (played by Amy Brenneman) intermittently narrates the whole film, and thank God. Without her occasional voice-overs, we’d have to face the fact she’s shafted by the script once a directorial-identification character shows up to ruin everything.

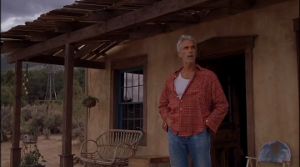

Bo’s father, Charley (Elliot) is a Koren War vet who took his three hundred dollar VA benefit out to the middle of nowhere and married a gorgeous, capable, beautiful, vision of the Goddess named Arlene (Joan Allen). The Grodens are entirely self-sufficient, paying in trade for what they can’t procure themselves. No phone, no electricity, no running water. Yet their house is a pristine gem of mid-century Americana: all cut wood and tile, with furniture salvaged from town dumps. There’s four years worth of food in the cellar, three years worth of firewood. As twelve-year-old Bo explains to the directorial identification character,

“My father’s philosophy is if you spend all your time working for someone else, you wont have any time to figure things out for yourself.”

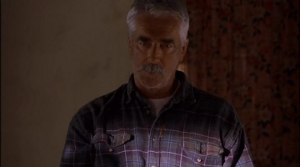

There’s just one problem: “That was the summer of my father’s depression.” Completely and inexplicably, it seizes him and refuses to let go, dampening the entire summer. All do their best to work around Charley’s condition and help him to work through it as best the can. Bo engages him verbally, while his best friend and old war-buddy George (J.K. Simmons) attempts to lead him out of it by setting a strong, silent type example. Arlene, being deeply in love with him, keeps constant tabs on his movements, lest he commit suicide, and is the only character strong enough to confront him about it directly.

Despite their obvious love, the Grodens are out of their league. Having built their life around overcoming physical hardships in some of the harshest country in North America, our family’s stymied by Charley’s mental ones. The first twenty minutes of this movie are a lot of them being stymied and a lot of Sam Elliot responding to it by sitting in a chair, staring into his hands, looking forlorn. To Scott’s credit, it’s not all that. Indeed, Bo dominates the first half of the film. Most of it seen through her perspective and these are the movie’s best scenes. Valentina de Angelis does a wonderful job animating her home-schooled-and-therefore-crazy-smart-but-still-a-twelve-years-old-girl character as Scott’s camera follows her through her typical day. She’s easily the most engaging little girl this side of Mindy Macready and I had high hopes that the whole movie would be all about her.

Enter the taxman, William Gibbs (Jim True-Frost), sent by Albuquerque to audit the Grodens for failing to file a return…seven years in a row. Unfortunately, Bill had a little trouble finding the place and, to hear him tell it, wandered in the desert for two days (not shown) before coming across a naked Joan Allen (which is shown…thankfully). Yeah, Arlene’s gardening in the nude, and I obviously can’t show you that…but I can show you the painting it eventually inspires.

So, yeah. Joan Allen gardening in the nude. Thanks for that, Off the Map. I appreciate it. Not as much as Bill, obviously, but I do. And I appreciate the fact Bo has to remind her mother to get dressed even more.

“We’re pretty casual around here,” Arlene says to Bill, after Charley’s wandered, naked and too depressed to care, through the house for his inevitable glass of water. (I didn’t appreciate the naked Sam Elliot so much…but maybe some of you will). And suddenly we’re in a fish out of water comedy directed without a hint of comic timing, so all the jokes feel awkward and forced instead of funny. Most of them are based around Bo’s attempts to become Bill’s Gal Friday. To her he clearly represents the much-talked-about Outside World. Bill is, in every sense, the Anti-Charley. An Easterner and recent migrant to the desert, Bill’s carrying around an invisible backpack-full of actual issues. Charley, the desert fox, lives (if the cinematography is to be believed) in paradise. So why’s he so damn depressed?

Unfortunately, the Grodens keep bees and, shocker, Bill got stung multiple times on his way up to their house, not noticing because…yeah…naked Joan Allen. He falls into shock and the Grodens, ever the good hosts, stand guard over him for the next however-many nights it takes him to sweat and shiver out the bee venom. There might’ve been some tension in this. I would’ve liked to see Charley shocked out of his funk by the superior funk-based powers of a dead body on the couch. But the things I like don’t generally make it onto movie screens. (Moreso these days, sure, but still…) Thanks to narrative convenience, Bill’s isn’t the kind of allergic reaction that closes up your throat up like a noose. Arlene even whips out her grandmother’s Hopi medicine kit so we know everything’s gonna be alright.

Indeed, Charley seems to sense his symbolic relationship with Bill. In the midst of Bill’s delirium he asks, “Have you ever been depressed?”

“I’ve never not been depressed.”

Bill reveals he saw his mother commit suicide at age six. “In the front hall…I opened the door with my back because I was carrying a pyramid home from school that I made out of foam core.” He turned around and boom, dead mom in the hall.

So, we’ve got a depressed Sam Elliot, an IRS man with a Spalding Gray-shaped chip on his shoulder, a precociously home-schooled twelve-year-old, and the woman they all love, trying desperately hold all this together. For about forty-five minutes, all this actually manages to hold the movie together. Problem being, Off the Map’s an hour and forty-five minutes long.

It’s a melancholy, meditative, mediocre kind of film, chalk full of water imagery (symbolic of transmutation) and landscape paintings. It asks only that you dive in and swim around in its mise-en-scène. It’s beautifully shot, fully utilizing the unique backdrops of its literally-picturesque landscape to capture both the stark vistas and the hidden riots of life behind every nook and cranny in the (real) great American desert. The Grodens are truly a part of their land and have found complete freedom in adapting to it. We can see in Bo’s intelligence, erudition, craftiness, and observational skill that they’ve done a damn good job raising a family under extraordinary circumstances. Their philosophy’s proved sound by the very status quo Charley’s depression interrupts.

So why is Charley so depressed? You’d think this would be a central mystery, a premise to hang all these landscape paintings on. But you’d be wrong. The movie never answers that question. “Fuck your questions,” it says. “Look at that sunset.” Fuck your questions, Joan Akermann’s script (based on her play) says, look at these people. Look at them act and react to each other. Look at good performance! See how they carry a film through even the most-pointless plot cul-de-sacs.

For example, Arlene convinces George to impersonate Charley and visit a psychiatrist, hoping he can hook the family up with some anti-depressants. Instead, George falls in his own taciturn kind of love with his psychologist (not shown)…a love Arlene shoots down as efficiently as any gunslinger, with a single line: “You should never confuse business with personal feelings, George.”

Damn, girl. That’s…”cold” seems the wrong word for this setting. “Hard” seems better. But, if George takes offense, he’s too much of a Good ol’ Boy to let it show. Instead, he falls for a delightful-looking young Mexican woman he meets on the street while taking Bo into town on a weekly shopping trip. When next we meet him, he says he’s dating that young woman. When next we meet him, they’re getting married in a nice little Catholic ceremony. (“I give you a companion,” the Priest says. “Not a servant. Love her as Christ loves the church.” Right the fuck on, padre. Bueno.) Their entire relationship takes place off screen and by this point, I’d begun to sense a pattern.

“But he’s a minor character,” you say. Okay. How about Bo. It’s her story, right? She’s narrating. She’s the one we spend the first half of the movie with. Through her interactions with the others, we get to see all sides of her multifaceted personality, and the other characters reactions to her draw each of them out, toward the horizon of three-dimensionality. Valentina de Angelis gives an absolutely beautiful performance, only annoying me after the film’s focus shifts.

To what, you ask? Why, the young yuppie, of course. Awakening from his delirium, he declares his love for Arlene…and I’m thinking, Alright. What we have here is the perfect horror movie set-up. The Anti-Charley slowly taking over Our Depressed Father’s life. Call it Married White Male since, soon enough, Bill’s wearing Charley’s clothes and doing all the manly things Charley’s been too depressed to get around to. If Bill and Arlene fell in love I could call this The Deserts of Madison County and be done with the whole damn thing.

Instead, Bill’s love turns out to be as chaste and non-physical as a monk’s love for the Virgin Mary. Having come out the other end of his personal cave, Bill emerges a changed man, something of a hero in this largely conflict-less story. Shunning his IRS job, Bill takes up Charley’s unused set of watercolor paints and begins an artistic career that will, eventually, carry him all the way to his death. (Not shown…because why show interesting stuff when someone can just tell the audience it happened?)

Let’s break all this down. In Story A we’ve got a paragon of Young Womanhood coming of age in…I think I heard Nixon on George’s car radio in one shot, so let’s just say “in the 70s.” Story B concerns a young man coming to terms with a traumatic memory that may or may not be real in the first place (the bee venom leaves this in question). Buried under all that, we find Charley down there in Story C, despite dominating nearly every scene in the film. He can’t help but dominate – he’s Sam Elliot, by God, and Sam Elliot here is an emotional black hole from which no one’s attention can escape.

I think I misunderstood Adult Bo when she said, “That was the summer of my father’s depression.” Off the Map puts the emphasis on the summer and tries to capture the hazy, fatigue-inducing energy of that longest and shortest season. It strives for a level of emotional verisimilitude that I commend wholeheartedly. Campbell Scott is a trained actor and it shows in the performances he wrung out of this cast. I just wish he’d deployed all this raw talent tactically, in the service of one story that everyone could stick with the whole way through.

Instead, the movie bludgeons us with woozy-cam close ups and one awkward social interaction after another. It’s like watching a live action Williams Street show on Adult Swim directed by Larry Clark. It’s like they ground up all these character studies into a find, sunset colored paste and slathered it across ninety minutes of movie like homemade hot sauce. Might be nice as a topping, but I’m not the kind of guy who calls that a main course.

Maybe you are, though. I don’t do this for me: I suffer so you don’t have to. Maybe you like movies that luxuriate in themselves and don’t really care whether you care or not. Movies that spend an hour and ten minutes ratcheting up emotional tension, only to deflate everything with a series of one-scene resolutions where characters stand around talking about stuff that happened off-screen. Maybe you like movies packed with obscure literary references.

In this case, it’s Richard Henry Dana, Jr’s Two Years Before the Mast, an 1840 classic of American literature detailing the glorious moments and horrific living conditions of nineteenth century sailors. It also described what was then called “Alta California,” a far-flung province of Mexico populated by small, coastal enclaves. Because of this, it became a best seller twice over once the Mexican-American war removed the “Alta” from California’s name, making it part of the United States…

Along with New Mexico. Hmm…Dana was the son of a wealthy family, educated in a private school by no less than Ralph Waldo Emerson. By 1831, Dana made it to Harvard, where he caught the measles that threatened his life and forced him to take a long sea voyage (the most effective measles treatment available to medical “science” of the time). He sailed – like Bill – out of Boston, and Bo spends the entire film fixated on Bill’s big city origins, frequently bringing up the sea and discussing the trip they will take to the big cities of the East Coast. As if her and Bill’s leaving together were a foregone conclusion…

Bill’s first watercolor is a three foot by forty-one foot mural of the Atlantic ocean meeting the sky, painted just for Bo. Akermann’s script makes sure even the slobbering proles catch her symbolism by having Adult Bo explain it all:

“I have of late been pondering that painting…It has struck me to view the ocean as the past, the sky as the future, and the present as that thin, precarious line where both meet. Precarious because, as we stand there, it curves under foot, ever changing.”

Off the Map starts out strong, tracing the curve of one young woman’s summer. Then we grow to realize Bo – for all her actress’ charisma – is the least-interesting character in the movie. Or so it would seem, since the movie stops tracing her curve in order to ink the other characters, deepening and shading them at Bo’s expense. I can see how, in its original form as a play, this would be an actor’s dream. It’s minimal dialogue allows everyone (aside from Bo – who, being a twelve-year-old-girl with a crush on the Exotic Outsider who fell into her family’s lap, can’t shut the fuck up) to communicate with their posture, their business, their body language. This is full-on Body Acting. You’ve heard of “on-screen chemistry?” This is Scott trying to power a movie with on-screen chemical reactions. It…kinda works…but it’s as much of a landscape painting as anything Bill churns out.

Off the Map starts out strong, tracing the curve of one young woman’s summer. Then we grow to realize Bo – for all her actress’ charisma – is the least-interesting character in the movie. Or so it would seem, since the movie stops tracing her curve in order to ink the other characters, deepening and shading them at Bo’s expense. I can see how, in its original form as a play, this would be an actor’s dream. It’s minimal dialogue allows everyone (aside from Bo – who, being a twelve-year-old-girl with a crush on the Exotic Outsider who fell into her family’s lap, can’t shut the fuck up) to communicate with their posture, their business, their body language. This is full-on Body Acting. You’ve heard of “on-screen chemistry?” This is Scott trying to power a movie with on-screen chemical reactions. It…kinda works…but it’s as much of a landscape painting as anything Bill churns out.

Off the Map‘s a great example of stellar performances from a great cast carrying a movie on their backs. If that’s your thing, check it out. Luxuriate in these performances. Or in New Mexico’s finer, naturally painted landscapes. Or you could turn off your TV and…oh, I don’t know…actually go to New Mexico. There’s no cinematic substitute for that feeling you get when its just you out there, alone, facing the curvature of the Earth.

![]()

![]()

![]()

You compared this to Gerry. That’s enough for me to never ever ever watch it. Thank you?

You’re…welcome…? But if it comes down to a choice between them, make mine Off the Map. Every time. Hands down.

You passed up Final, for this? Really?

I checked out IMDB just to see what it is, and it sounds far more of a movie that I would expect to see here. Starring Denis Leary, it sounds like a chamber drama with shades of Chronenbergian medical experiementation. Something much more intriguing IMO.

I was being a little disingenuous there – it’d be more accurate to say “I was made aware Final exists thanks to this movie, which reminded me Campbell Scott existed. Wasn’t kidding about the Hamlet thing, though – that and Big Night were all I knew him from until this movie forced me to look up him again. “Hot damn,” I said, “the dude’s still kicking. And acting/directing double threat.” Usually TV movies come either at the beginning or end of a director’s career trajectory and I was glad to see Scott got out of the way at the beginning.

I’ll consider this another vote for a review of Final.